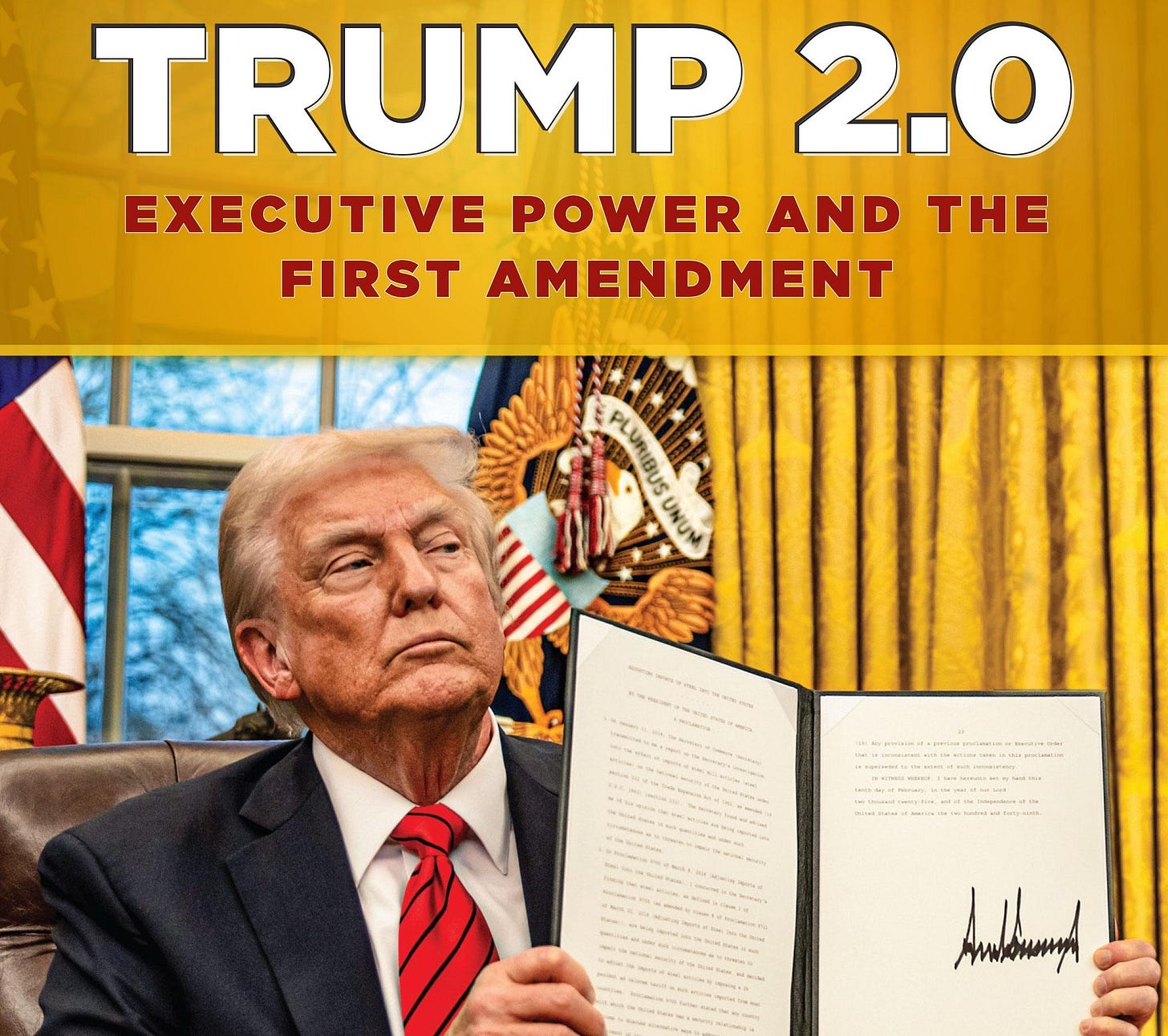

Book review: ‘Trump 2.0: Executive Power and the First Amendment’

First Amendment News 497

In what follows, Stephen Rohde offers a review essay of Professor Timothy Zick’s recently released book, Trump 2.0: Executive Power and the First Amendment (Carolina Academic Press, 2026). It is the first review of the book, and I’m grateful to Mr. Rohde for his prompt and thoughtful reflections.

By way of full disclosure: Though Professor Zick has written for FAN, and while I have commented on his work several times, he had no prior knowledge of the Rohde review or any involvement with it. Likewise, the views expressed are entirely those of Mr. Rohde sans any content control on my end. With that, his review is proffered for your consideration.

— rklc

Among his worst character flaws wreaking havoc on our democracy, President Donald Trump’s hypocrisy has no bounds. During his second inaugural address on Jan. 20, 2025, he promised:

After years and years of illegal and unconstitutional federal efforts to restrict free expression, I will also sign an executive order to immediately stop all government censorship and bring back free speech to America.

As promised, later that very day, he issued an executive order declaring “Government censorship of speech is intolerable in a free society.”

If only.

Instead, Trump has issued more than forty executive orders, fact sheets, and presidential memoranda, along with scores of enforcement actions dutifully issued by the obedient federal officials he has appointed, that abridge the First Amendment rights of millions of Americans and foreign visitors.

In August, he issued yet another executive order titled “Prosecuting Burning of the American Flag.”

In a garbled, revealing, and inaccurate comment, Trump boasted, “We took the freedom of speech away because that’s been through the courts and the courts said, you have freedom of speech.”

Seventeen ways Trump violated the First Amendment

In the timely and engaging new book Trump 2.0: Executive Power and the First Amendment, Tim Zick writes, “Trump 2.0 policies and actions have had broad censorious and chilling effects” that represent “the greatest governmental threat to the First Amendment since the McCarthy Era of the 1950s.”

The book makes a valuable contribution by bringing together a compendium of Trump’s most egregious First Amendment violations to date. A review of Zick’s complete list of these violations is a shocking reminder of just how extensive, breathtaking, and dangerous they are to our constitutional democracy.

Trump and his cohorts have violated the First Amendment by:

retaliating against law firms for their advocacy and representation of specific clients;

investigating and indicting current and former government officials based on their criticism of the President or expression of disfavored ideas;

firing federal prosecutors and Federal Bureau of Investigation employees for working on cases relating to President Trump and the Jan. 6, 2021 Capitol riot;

terminating billions of dollars in federal funding to universities in an effort to alter their ideological cultures and control their core academic operations;

conditioning federal research and other funding on the agreement not to practice or promote “diversity, equity, and inclusion” or “gender ideology” and to teach only “patriotic” curricula in K-12 schools;

arresting, detaining, and subjecting to deportation international students and foreign scholars based on their viewpoints and political activism, and revoking the visas of foreign nationals based on political expression;

retaliating against the press by excluding specific media outlets from White House events based on their viewpoints and reporting;

threatening to revoke broadcast licenses based on networks’ editorial decisions; restricting reporters’ access to unclassified defense-related information held by the Pentagon;

suing newspapers and publishers for defamation, consumer fraud, and “election interference”;

defunding libraries and public broadcasters;

scrubbing historical, scientific, and other data from federal agency websites;

ordering the removal of “anti-American” displays in national museums;

terminating grants for scientific research and removing scientific papers from government databases because the research referred to forbidden terms relating to race, gender, or environmental justice;

threatening to sanction advocates who assist officials with prosecutions in the International Criminal Court; directing the Attorney General to prosecute individuals who burn the U.S. flag because the expressive act is “uniquely offensive and provocative” and communicates “contempt, hostility, and violence against our Nation;”

declaring “Antifa” a “domestic terrorist organization” and directing federal agencies to investigate and prosecute political violence linked to the expression of “anti-Americanism,” “anti-capitalism,” “anti-Christianity,” “extremism on migration, race, and gender,” and “hostility towards those who hold traditional American views on family, religion, and morality;”

suggesting that individuals protesting immigration raids are members of “organized crime” syndicates; and

federalizing and deploying the National Guard and active-duty United States Marines to several American cities in response to public protests.

Executive abuses of power with the stroke of a pen

Timothy Zick, the John Marshall Professor of Government and Citizenship at the William & Mary Law School, teaches courses on the First Amendment, constitutional law, and academic freedom. He has written six books and scores of articles on freedom of expression.

The premise of his latest book is that as “Trump has demonstrated, with the stroke of a pen the President can issue new interpretations of federal laws and institute policies that affect not just government institutions but vast swaths of the private sector as well.” The Trump Administration’s second act “is a stark reminder that executive power can significantly threaten or violate First Amendment rights” and “may pose even greater threats to free expression than ordinary legislative acts.” Trump “has shown the Nation’s Chief Executive can use his powers to direct, influence, suppress, and coerce private expression.” As Trump has demonstrated, “the laws of Congress may be of little consequence if a President chooses to ignore them and Congress does not respond.”

By the time he finished writing his book, Zick counted more than fifty lawsuits raising First Amendment claims against the Trump administration by law firms, universities, media, scientists, international students, professional associations, and others impacted by executive actions. To examine these controversies, Zick curates excerpts from important court decisions, along with the texts of key executive orders, pleadings, agency compliance letters and responses, public comments in agency proceedings, and other firsthand materials. Since few readers have read any of these original documents, they are extremely helpful in understanding what is happening in real time.

To complement his book, Zick has compiled a comprehensive online repository — updated weekly — of First Amendment-related Trump 2.0 executive orders, lawsuits challenging them, and informative commentary, available at Trump 2.0: Executive Power and the First Amendment, First Amendment Watch. Overall, one appreciates how American institutions, lawyers, and judges are playing an indispensable role in defending our constitutional democracy.

Zick’s goal

In his analysis, Zick addresses several fundamental First Amendment questions posed by Trump’s assault on free speech: What is the relationship between executive power and free expression? Are executive orders a form of government speech or a means of suppressing private expression? What kinds of governmental actions constitute governmental suppression or censorship of speech forbidden by the First Amendment? To what extent can the president use threats to terminate federal funding or other actions to influence or coerce expression? How well-equipped are First Amendment doctrines and principles to respond to new threats by presidents and executive agencies under their direction?

Zick’s goal — which he admirably achieves — is to fill an important gap in the study of the First Amendment by documenting “the variety of ways in which executive power can independently threaten freedom of expression, and how executive actions differ from legislation in that respect.” He also addresses “how instructors, scholars, and students can use Trump 2.0 events to deepen their understanding of freedom of expression and perhaps suggests revisions to First Amendment doctrines.”

While his book is structured primarily as a casebook for use in law schools and other academic settings, by writing in a conversational style free of arcane legalisms Zick succeeds in making it “important to anyone who supports, defends, relies upon, or indeed exercises First Amendment rights.” As he writes, “We ought all to be aware of current executive challenges to free expression and how various actors — including courts, the press, lawyers, universities, and other regulated parties — have responded to them.” To highlight the complexities of these situations, each chapter contains a “problem exercise” that encourages readers to explore the practical challenges of responding to Trump’s dangerous executive actions.

Zick has done us all an enormous favor by organizing Trump’s First Amendment violations into a well-documented, systematic survey. He imagines how helpful it would have been to have had a contemporaneous record of McCarthy Era violations of First Amendment rights. As he puts it, a “repository of the various executive actions affecting Americans’ First Amendment rights during the Trump Era is an invaluable resource for current — and future — students of this period.” By “students” I take him to mean everyone who cares about preserving meaningful protections for the freedom of speech, press, and assembly, and the right to petition the government for redress of grievances.

Zick also puts Trump’s conduct in a historical context. “As historians and scholars have observed,” he writes, “presidents have threatened or violated First Amendment rights throughout American history.” He cites the examples:

John Adams prosecuted his wartime political opponents, including members of the press, under federal “sedition” laws;

Woodrow Wilson used the Sedition Act and Espionage Act to convict and imprison one thousand wartime activists and prosecute twice that many;

Richard Nixon threatened to subject his “enemies list” to IRS investigations and other sanctions;

Barack Obama prosecuting reporters and whistleblowers in connection with national security investigations; and

Joe Biden pressured social media platforms to remove controversial posts about the 2020 presidential election, Covid-19 misinformation, and other content.

Executive orders and executive violations

Make no mistake: “[I]n terms of threats to free expression,” Zick is convinced that “Trump 2.0 has been historically exceptional. No past president’s actions affecting expression likely would have merited a chapter, much less an entire book, after only the first 100 days of a term.”

Zick explains how Trump and the agencies over which he exercises dictatorial control have used a variety of tactics to suppress disfavored speech, bring the media to heel, alter the ideological culture on university campuses, influence scientific inquiry, and affect expression “across the Nation and beyond including in boardrooms, classrooms, laboratories, libraries, scientific journals, museums, and international courts.”

First, many executive orders rely on threatened or actual termination of federal funding as an enforcement mechanism. Federal funding affects nearly every aspect of American life, including education (at all levels), commerce, agriculture, health care, immigration, the practice of law, broadcasting, and scientific research. “The Trump administration has used a chainsaw rather than a scalpel when terminating funds for alleged violations of federal law.”

Second, in many instances, “the Trump administration has failed to provide the process required under federal law to deny or terminate federal funding,” thereby enhancing the coercive and chilling effects of agency enforcement actions. “By accelerating the denial of millions of dollars in federal funding, grantees have little time or recourse to contest often vague allegations or charges of wrongdoing prior to the denial or termination.”

Third, because many of Trump’s executive orders lack meaningful specificity about concepts and terms, including “DEI,” “radical gender ideology,” “patriotic” curricula, and “divisive ideology,” federal grantees cannot be certain which words, phrases, or ideas will trigger a denial of often-critical funding. “Vagueness of the standards in executive orders has produced significant uncertainty for universities, hospitals, businesses, and other funding recipients” which “in turn, has led to significant instances of anticipatory compliance — including changes in expression on a scale far beyond what federal antidiscrimination or other laws require.”

Fourth, for many of these reasons, the executive orders “have engendered repressive fear in federal fund recipients and those who have been or might be targeted,” born of direct or veiled demands for loyalty and the specter of punishment for dissent. Thus, “words and phrases must be removed, lectures canceled, and ‘deals’ inked that trade away First Amendment rights and academic freedom for relief from facially retributive, disproportionate, and likely unconstitutional Executive Orders.” By relying on “anticipatory compliance,” fear, vagueness, and coercion, “President Trump’s executive orders and agency enforcement actions have produced far more regulation and suppression of speech than ordinary executive action — which is constrained by (among other things) resource considerations and the obligation to comply with federal laws.”

Into the breach

The good news is that there is an extensive arsenal of robust, well-established Supreme Court precedents that challengers are effectively using to nullify Trump-era violations of the First Amendment. Zick expertly explains them in the following seven ways:

Viewpoint discrimination

Although the government can communicate its own views, it is generally prohibited from suppressing the viewpoints of private speakers. First Amendment doctrine treats laws that suppress specific subjects and target particular viewpoints as presumptively unconstitutional. These “content-based” speech regulations must meet a “strict scrutiny” standard that requires them to further a compelling governmental interest and be the least speech-restrictive means of doing so. The Court has described viewpoint discrimination as “an egregious form of content discrimination.” The government “must abstain from regulating speech when the specific motivating ideology or the opinion or perspective of the speaker is the rationale for the restriction.” As the Court famously observed more than eighty years ago:

If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.

Retaliation based on protected expression

The First Amendment prohibits government officials from subjecting individuals to retaliatory actions for engaging in protected speech. To succeed on a First Amendment retaliation claim, a plaintiff must typically prove that they engaged in a constitutionally protected activity, that the government’s actions would “chill a person of ordinary firmness” from continuing to engage in the protected activity, and that the protected activity was a substantial motivating factor in the retaliation.

Vagueness

The Supreme Court has observed that it is “a basic principle of due process that an enactment is void for vagueness if its prohibitions are not clearly defined.” As the Court has observed, “[v]ague laws may trap the innocent by not providing fair warning.” The failure to provide clear standards raises the specter of arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement. Vague regulations may also “chill” expression by causing speakers to “steer far wider of the unlawful zone . . . than if the boundaries of the forbidden area were clearly marked.” In particular, the Court has emphasized the chilling effects of broad governmental directives and investigations aimed at suppressing disfavored viewpoints or ideas.

‘Jawboning’ and informal speech suppression.

Suppression and censorship of expression can take many forms. Aside from regulations that directly prohibit or restrict expression, governments sometimes rely on more indirect forms of speech suppression, known as “jawboning.”

In the 2024 unanimous decision, National Rifle Ass’n v. Vullo, the Supreme Court held that New York officials violated the First Amendment when they used informal communications and indirect pressure against regulated businesses to prevent them from associating with the National Rifle Association. The Court held that “[a] government official cannot coerce a private party to punish or suppress disfavored speech.” Indeed, owing to how the Trump Administration is abusing executive power, Zick believes Vullo “could turn out to be the most important First Amendment precedent of the Trump era.”

Unconstitutional conditions

One way the government can apply pressure to control expression is to condition federal funding on a grantee’s agreement not to engage in certain speech or associational activities. While the government is not required to fund a particular activity, if it decides to do so, it cannot deny or withdraw funding on a basis that infringes on an applicant’s First Amendment or other constitutional rights. And although government can restrict the use of federal funds to activities it chooses to support, it cannot “leverage funding to regulate speech outside the contours of the funding program itself.”

First Amendment rights of noncitizens

The Trump administration has arrested, detained, and initiated deportation proceedings against several international students and scholars who have engaged in pro-Palestine political advocacy. Previously, the Supreme Court has indicated that “[f]reedom of speech and of the press is accorded aliens residing in this country.” However, it has not clarified the precise relationship between enforcing the nation’s immigration laws and the First Amendment. In particular, the Court has not decided whether noncitizens in the U.S. enjoy the very same First Amendment rights as citizens. Lower courts have issued conflicting decisions on this issue. The Trump administration has been exploiting this uncertainty.

Free flow of information

The First Amendment protects the right to gather, distribute, and receive information. The Supreme Court has sometimes collectively referred to these activities as the “free flow of information.” The Trump administration has removed scientific and other data from government websites, restricted scientific research, defunded public broadcasters and libraries, and removed books from school libraries. A leading First Amendment commentator, Alexander Meiklejohn, wrote, “the point of ultimate interest is not the words of the speakers, but the minds of the hearers.”

The Supreme Court has emphasized that discourse on matters of public concern must be “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” The “First Amendment goes beyond protection of the press and the self-expression of individuals to prohibit government from limiting the stock of information from which members of the public may draw.” The Court has warned against governmental efforts “to control the flow of ideas to the public” and observed that “the State may not, consistently with the spirit of the First Amendment, contract the spectrum of available knowledge.” In sum, the “right of citizens to inquire, to hear, to speak, and to use information to reach consensus is a precondition to enlightened self-government and a necessary means to protect it.”

‘A serious contemporary analysis’

As Professor Zick persuasively demonstrates, if the Supreme Court remains true to its ample long-standing precedents upholding these fundamental First Amendment principles, Trump is in a lot of trouble.

In writing Trump 2.0: Executive Power and the First Amendment, Zick has performed a profound public service. It is said that “journalism is the first rough draft of history,” offering a raw, tentative account of fleeting events sealed in a time capsule for historians to excavate and study in the future. But Zick’s commendable book is hardly a rough-draft, and its audience is not a future generation. It is a serious contemporary analysis by a leading expert on the First Amendment sounding an insistent alarm that we ignore at our peril.

Brandeis’ admonition

In 1927, in his concurring opinion in Whitney v. California (joined by Justice Holmes), Justice Louis Brandeis reminded us:

Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State was to make men free to develop their faculties, and that, in its government, the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary.” He described how the Founders “valued liberty both as an end, and as a means. They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness, and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth. . . .

The Founders believed:

that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty, and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government.” He warned that “order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies, and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.

Today, Brandeis would surely be among the justices condemning Trump’s wholesale violations of the First Amendment. Frankly, shouldn’t all the justices be doing that?

Stephen Rohde is a writer and political activist. He practiced civil rights and civil liberties law for almost 50 years. He previously served as Chair of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California, and currently is Special Advisor on Free Speech and the First Amendment for the Muslim Public Affairs Council. He is also the author of “American Words of Freedom,” “Freedom of Assembly,” and co-author of “Foundations of Freedom.” He recently released Speaking Freely, a First Amendment Podcast.

2025-2026 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

Chiles v. Salazar (argued: Oct. 7)

Olivier v. Brandon (argued: Dec. 3)

First Choice Women’s Resource Centers, Inc. v. Platkin (argued: Dec. 2)

National Republican Senatorial Committee v. Federal Election Commission (argued: Dec. 9)

Pending petitions

360 Virtual Drone Services LLC v Ritter

Dershowitz v. Cable News Network

Emergency docket (‘Shadow docket’)

Margolin v. National Association of Immigration Judges (application for a stay)

Chamber of Commerce v. Sanchez (application withdrawn)

Free-speech related

Trump v. Carroll (Federal Rules of Evidence speech-related case)

Petitions denied

Cambridge Christian School, Inc. v. Florida High School Athletic Association, Inc.

Hartzell v. Marana Unified School District

Evans Hotels, LLC v. Unite Here! Local 30

Last Scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of FIRE.