Overview of equality, free speech & LGBTQ+ rights starting with the ‘One’ case

First Amendment News 486

In an earlier post, I wrote about a cert petition (a “PR ploy”) in which First Amendment claims are being raised to urge the Court to overrule its landmark gay marriage ruling in 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges. It is against that backdrop that I thought I’d say a few words about some LGBTQ First Amendment cases that have come before the Court — some of the more striking ones seldom, if ever, make their way into casebooks or even treatises on free speech.

What follows is excerpted and abridged from a First Amendment casebook I hoped to coauthor with a few others until one of the contributors bailed on us in the final hours, thus killing the project.

That said, some of my work can still be put to good use, or that is my hope.

Free speech and the equality principle

“The principle of equality, when understood to mean equal liberty, is not just a peripheral support for the freedom of expression, but rather part of the ‘central meaning of the First Amendment.’”

Those are the words of the late professor Kenneth Karst — words contained in a famous law review article he wrote titled “Equality as a Central Principle in the First Amendment.”

The idea of an equality (or anti-discrimination) principle being key to much free speech law can be seen in any variety of doctrines, ranging from that of content neutrality to public forum analysis. That said, there is at the same time a tension between the liberty principle of the First Amendment and the equality principle of the Fourteenth Amendment — as evidenced by, among other things, the Court’s handling of hate speech.

Unlike Equal Protection law, where there are categories of law specifically dealing with racial discrimination and LGBTQ+ discrimination, there is no real doctrinal counterpart in First Amendment law, though such discrimination has sometimes shaped a body of First Amendment law. This is especially true in the free speech context.

Related resources

Harry Kalven, The Negro and the First Amendment (1965).

David Greene and Shahid Buttar, “The Inextricable Link Between Modern Free Speech Law and the Civil Rights Movement,” Electronic Frontier Foundation (March 8, 2019).

Carlos A. Ball, The First Amendment and LGBT Equality A Contentious History (2017).

Paul Siegel, “Lesbian and Gay Rights as a Free Speech Issue: A Review of Relevant Caselaw,” 21 J. Homosexuality 203 (1991).

Dale Carpenter, “Born in Dissent: Free Speech and Gay Rights,” 72 SMU L. Rev. 375 (2019).

The case of the magazine that brought gay life out of the closet

Imagine being gay in 1956. You live in a secret world. If discovered, your intimate life could get you arrested and thrown in jail — or worse. If outed, you could lose your job. Sharing time with others like you most likely means going to a dark and dingy bar on the outskirts of town. And if your parents and trusted friends know about you, it is all kept very secret. In other words, you live in the closet.

That America was commonplace to gay people. Even publishing and mailing a “pro-homosexual” non-obscene magazine could trigger an FBI investigation and U.S. Postal censorship. Again, we’re talking about non-obscene material, even by 1957–58 legal standards (see Roth v. United States (1957)). Even so, the government took aim and refused to allow such magazines to be sent in the mail, which could mean the death of any such magazine. (The Masses, an avant-garde leftist magazine, died in 1917 after the post office refused to send it).

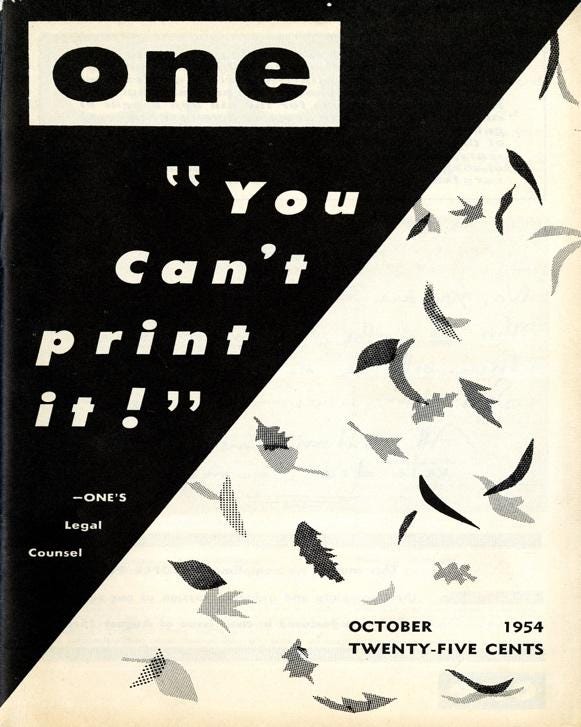

All of this brings us to ONE, a gay and lesbian magazine. As author, journalist, and activist Jonathan Rauch recounted: “ONE was the country’s first openly gay magazine of ideas. It debuted in 1953 with serious articles on subjects like ‘homosexual marriage.’ (In 1953!) It did not publish explicitly sexual content or anything that approached the boundaries of pornography.”

ONE took its name from a poem by Thomas Carlyle, a Scottish philosopher and writer. The line: “A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one.” To be “one,” then, meant to be “one of us” — a proud gay, lesbian, or transgender person.

Back then, to print such a publication, and to house an office where it was produced, was to risk trouble. And trouble came in 1954 when the postmaster in Los Angeles tagged ONE’s October issue as “obscene, lewd, lascivious and filthy.” In other words, it could not be sent in the U.S. mail — and in an era without alternative methods of correspondence, like FedEx or e-mail, that essentially meant it couldn’t be sent at all.

And why? To start, it contained a poem about gay cruising (“Lord Samuel and Lord Montagu”), a lesbian-love short story (“Sappho Remembered”), and an ad for The Circle magazine, which printed gay romance stories. Additionally, Rauch has aptly noted, there was more:

…the banned issue’s cover article was a critique of, you guessed it, the government’s censorship. The cover announced “You Can’t Print It!” and the article walked through the many restrictions imposed on the magazine. The government censored the article objecting to government censorship.

1957: ACLU absent

When censorship came in 1957, the ACLU did not come to the rescue of ONE. In a statement released by its board of directors on Jan. 7, 1957, the ACLU stated:

The American Civil Liberties Union is occasionally called upon to defend the civil liberties of homosexuals. It is not within the province of the Union to evaluate the social validity of laws aimed at the suppression or elimination of homosexuals.

It fell to ONE’s in-house counsel and the unnamed author of “You Can’t Print It!,” Eric Julber, to take the government to federal court in ONE v. Olesen.

Again, from Jonathan Rauch:

Federal district and appellate courts delivered defeats in stinging terms, leaving no doubt that the government’s censorship was message-specific. The district court’s decision held, “The suggestion advanced that homosexuals should be recognized as a segment of our people and be accorded special privilege as a class is rejected.”

When the court of appeals for the Ninth Circuit weighed in, it focused on the “Sappho Remembered” short story: “the young girl gives up her chance for a normal married life to live with the lesbian. This article is nothing more than cheap pornography calculated to promote lesbianism.” That ended the matter.

When the case went to the Supreme Court, something very unexpected happened. On Jan. 13, 1958, the justices summarily reversed by way of a per curiam opinion, which in its entirety read:

The petition for writ of certiorari is granted and the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit is reversed. Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476.

Think about it: Julber’s First Amendment victory on behalf of free speech rights for the LGBTQ+ community was:

11 years before the Stonewall riots;

15 years before Lambda Legal was founded;

15 years before the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders in the DSM-II Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders;

20 years before San Francisco elected Harvey Milk to office (the first openly gay man to be elected to a political office in California . . . and then murdered);

21 years before the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights occurred;

45 years before Paul M. Smith (a noted Supreme Court litigator) convinced the Supreme Court to strike down a “homosexual conduct” sodomy law in Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003); and

57 years before Mary L. Bonauto persuaded the Supreme Court to strike down anti-same-sex marriage laws in Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015).

This early victory was a First Amendment victory — and at a time when everyone, save ONE and Julber, thought it impossible.

Subsequent Supreme case

In Manual Enterprises v. Day, 370 U.S. 478 (1962), the Court ruled (6-1) that three homoerotic physique magazines (MANual, Trim, and Grecian Guild Pictorial) were not obscene and could not be banned from the U.S. mails.

In the course of his arguments on behalf of the petitioners, Stanley Martin Dietz (“the first lawyer to make an argument in favor of gay rights” before the Supreme Court) argued that “[t]here is no community that has no homosexuals.” (See James Kirchick citation below).

Writing for the majority, Justice Harlan revisited the Court’s view of what constituted obscenity. Though the lower courts had argued that the intended audience of the magazines (homosexuals) rendered the material obscene, Harlan concentrated on whether the materials were “so offensive on their face as to affront current community standards of decency — a quality that we shall hereafter refer to as ‘patent offensiveness’ or ‘indecency.’” If the materials lacked that quality, the Court need not consider the question of “audience.”

Referencing the Hicklin test, Harlan argued that for materials to be obscene required two things: they were patently offensive, and an appeal to prurient interest. Therefore, he reasoned, “The Court of Appeals was mistaken in considering that Roth made ‘prurient interest’ appeal the sole test of obscenity. . .” Harlan then referenced the Roth standard that required a determination of the relevant “community.” On that score, he concluded that since the law in question dealt with the national mail, the relevant community was a national audience. As to Roth’s “prurient appeal, Harlan declared. “[We] need go no further in the present case than to hold that the magazines in question, taken as a whole, cannot, under any permissible constitutional standard, be deemed to be beyond the pale of contemporary notions of rudimentary decency.” He also noted that “these portrayals of the male nude cannot fairly be regarded as more objectionable than many portrayals of the female nude that society tolerates. Of course, not every portrayal of male or female nudity is obscene.”

Resources

James Kirchick, Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (2022), pp. 269-273

Judith Valente, “Making A Living Defending the Pornographers,” The Washington Post (Jan. 11, 1978):

During the 1950s, Dietz represented several homosexual men who charged that they had been brutalized by D.C. police. Herman Womack, a local philosophy professor and a homosexual, hired Dietz as his attorney when he began encountering difficulties with the Post Office for selling homosexual magazines through the mail. When Womack’s company MAN-ual Enterprises, sued the postmaster general, Dietz took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a landmark decision, the high court ruled that neither the Postmaster General, nor any U.S. agency except a federal court, had the authority to determine what is obscene.

The next case, Rowland v. Mad River Local School District

In order to get some perspective on this long-overlooked First Amendment case, it is helpful to have some sense of the history surrounding LGBTQ+ rights at the time when Marjorie Rowland found herself at the crosswinds of a controversy over her sexual identity. Note that her case, which began in 1974, occurred some 29 years before the Supreme Court ever extended any constitutional rights to LGBTQ+ persons as it first did in Lawrence v. Texas, 539 US 558 (2003).

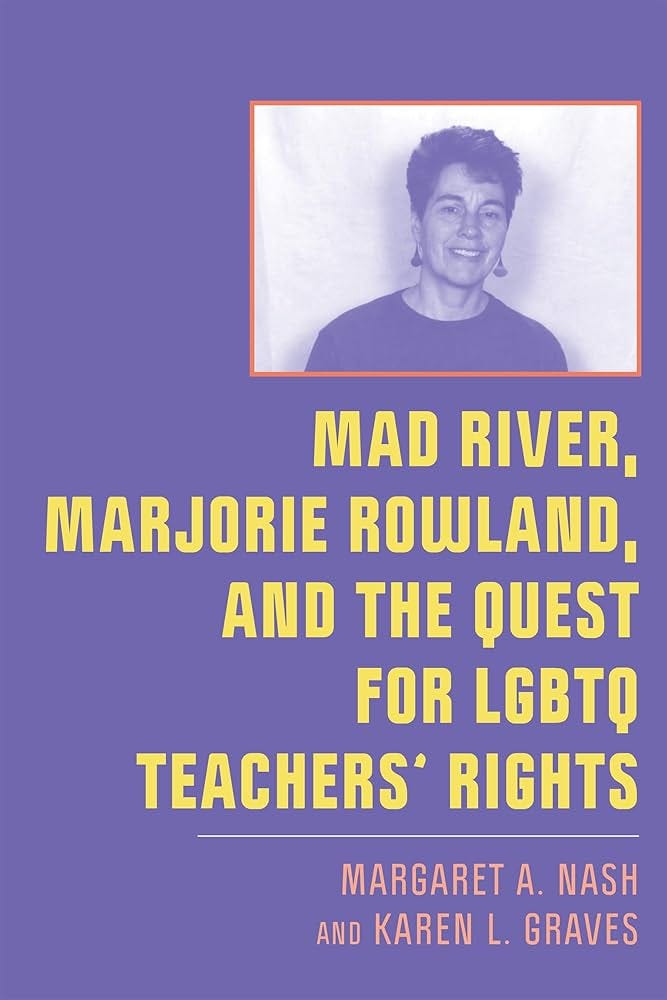

What follows is excerpted (with permission) from Margaret A. Nash and Karen L. Graves, Mad River, Marjorie Rowland, and the Quest for LGBTQ Teachers’ Rights:

The controversy

Marjorie Rowland began work as a counselor at Stebbins High School in Dayton, Ohio, in August 1974. In November, she told her secretary that two particular students did not need to have special permission to see her and that if Rowland was available, the secretary should allow either of those students to come in. The reason, Rowland disclosed in confidence, was that each of these students had come out to their parents as gay, the parents had not responded well, and the students needed support. The secretary peppered Rowland with questions, leading to Rowland saying that she was bisexual and was currently in love with a woman.

She was suspended from her nontenured position as a high school guidance counselor. In April 1975, the respondent school district acting through its school board decided not to renew her contract.

The history

At the end of World War II, Cold War politics framed the most repressive period in U.S. history for gay and lesbian citizens, and educators became a particularly vulnerable target. One reason for the increased repression was the increased visibility of homosexuality. Alfred Kinsey published his famous study The Sexual Behavior of the Human Male in 1948, documenting that more than a third of the men in his study had had at least one homosexual experience. Many civic leaders and citizens were horrified and pushed for more punitive laws that often included a psychiatric diagnosis. In some states, by law, if you had homosexual tendencies, whether or not you had engaged in homosexual behavior, you were labeled a sexual psychopath.

As a result, this period was marked by a widespread purge of gay and lesbian teachers, professors, and students. The most relentless attack occurred in Florida during the Johns Committee investigations. Between 1957 and 1963 the state investigative committee actively pursued lesbian and gay schoolteachers, subjected them to interrogation, fired them from teaching positions, and revoked their professional credentials. By 1963 the committee reported that it had revoked seventy-one teachers’ certificates with sixty-three cases pending and had files on another hundred ‘suspects.’ A combination of factors led to the committee’s demise in 1965, but, as Stacy Braukman shows, the ideology that powered its crusade simply went underground. A 1977 reprisal in Miami pushed Florida to the center of the national spotlight on the gay rights movement.

Some communities in the United States began to inch toward civil rights protections for gay and lesbian citizens in the 1970s, overturning sodomy laws and prohibiting job discrimination. This political action triggered antigay organizing by conservative political groups. Among all public employees protected by newly minted antidiscrimination laws, lesbian and gay schoolteachers drew the most contentious reaction.

In 1977 and 1978 national attention was riveted on the gay rights battles taking place in Miami and California. In Florida, activists challenged a law that protected gay men and lesbians from discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations, strategically narrowing the scope of the referendum to focus on gay and lesbian teachers. In California, the referendum was based entirely on the question of who could teach in public schools.

The Florida referendum was a resounding defeat for the gay rights movement. Reporters characterized the vote as a ‘stunning setback’ for gay rights activists that would reverberate across the nation. It was followed by similar retrenchment in Minnesota, Kansas, and Oregon. Clearly, the political tide had turned, making the 1978 statewide vote in California increasingly important. There, gay rights groups organized effectively while antigay forces overextended their political reach, targeting all teachers who supported gay rights. This time voters rejected the referendum, handing the gay rights movement a critical victory.

At the same time, however, state senator Mary Helm introduced a bill in Oklahoma that was a virtual twin of the California law. It passed in the lower house by a vote of 88–2 without debate and was approved in the state senate unanimously. The new law allowed school districts in Oklahoma to fire gay men, lesbians, and any other educator who engaged in ‘public homosexual conduct,’ defined broadly as ‘advocating, soliciting, imposing, encouraging or promoting public or private homosexual activity in a manner that creates a substantial risk that such conduct will come to the attention of schoolchildren or school employees.’ In other words, the law prohibited teachers from supporting gay rights.

The National Gay Task Force (NGTF) challenged the law on multiple grounds: that it violated freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom of religion, the right to privacy, the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and the fact that the law was too vague and too broad. A federal district judge upheld the law, and the case went to the Tenth Circuit Court on appeal. In a 2–1 decision, the appellate court struck down the part of the law that restricted free speech. The dissenting judge James Barrett was furious, writing that a teacher who advocated on behalf of gay rights was less deserving of constitutional protection than one who advocated ‘violence, sabotage and terrorism.’

When the case reached the Supreme Court, six justices voted to hear the case. The court had a history of turning away cases brought by gay citizens who wanted to claim civil rights. In this case, the appellate court’s decision in favor of gay rights advocates would stand unless the Supreme Court ruled otherwise. Board of Education v. National Gay Task Force, 470 US 903 (1985) [argued by Laurence Tribe for Appellees] thus became the first Supreme Court case to address gay and lesbian teachers. Due to Justice Lewis Powell’s absence, the decision was tied 4–4, meaning that the NGTF victory at the appellate court was affirmed. The part of the law that infringed teachers’ freedom of speech was ruled unconstitutional.

Prior to the political organizing in Florida, California, and Oklahoma, individual teachers had begun challenging dismissals based on their sexual orientation in court. Backed first by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and then the National Education Association (NEA), plaintiffs fighting for their jobs tested legal arguments designed to keep LGBT educators out of schools. These early decisions turned on morality and privacy assumptions that had long circumscribed all teachers’ autonomy and employment rights. In some cases, teachers gained ground in the effort to secure nondiscriminatory employment protections, but, as Jackie Blount has observed, in all cases the individual teachers whose jobs were on the line were displaced.

Three of these cases reached the Supreme Court. In 1972 Joseph Acanfora was completing his student teaching assignment at Penn State when, as part of a news story on the university’s gay student group, he noted that he was gay. College officials subjected him to intense scrutiny regarding his character before forwarding his application for a teaching certificate to the state department of education. Acanfora accepted a job teaching eighth-grade science in Montgomery County, Maryland.

About a month into the school year, the Pennsylvania Department of Education held a news conference, announcing it was approving Acanfora’s request for a teaching certificate; Acanfora’s principal promptly removed him from his teaching duties. Although there was strong community support for Acanfora, the district court handed down a mixed opinion. It protected homosexuals’ right to teach but noted that Acanfora had violated the ‘duty of privacy’ he was to maintain as a public schoolteacher. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected that reasoning and upheld Acanfora’s right to freedom of speech. But it held that his dismissal could stand, given that he had failed to list his membership in the student group Homophiles of Penn State on his job application. The Supreme Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari (cert.) in October 1974, and Acanfora left teaching.

1977 petitions to the Supreme Court

In October 1977 the Supreme Court denied cert. in two more cases: Gish v. Board of Education of the Borough of Paramus and Gaylord v. Tacoma School District No. 10. James Gaylord, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Washington, was a high school history teacher who had established a strong record of teaching over a twelve-year period. He had not disclosed information about his sexual orientation and was not charged with any sort of immoral conduct, but when his vice principal asked if he was gay, he said yes. Gaylord was fired in December 1972 on charges of ‘immorality.’ The Supreme Court of Washington upheld the dismissal on the basis of Gaylord’s status as a gay man, a ruling the U.S. Supreme Court did not review.

That same day, the court denied cert. in Gish. In 1972 veteran high school English teacher John Gish organized the Gay Teachers Caucus of the NEA. Later that year, the Paramus, New Jersey, school board ordered Gish to take a psychiatric examination. Gish refused. Supported by the ACLU, he began a five-year legal journey that ended when the Supreme Court refused to hear the case, leaving the New Jersey Superior Court’s decision intact. Relying on the 1952 Adler v. Board of Education of the City of New York ruling that had since been superseded, the New Jersey court found that school boards maintained wide latitude in determining the fitness of teachers. They considered Gish’s “actions in support of ‘gay’ rights’ a deviation from ‘normal mental health which might affect his ability to teach, discipline, and associate with students.’

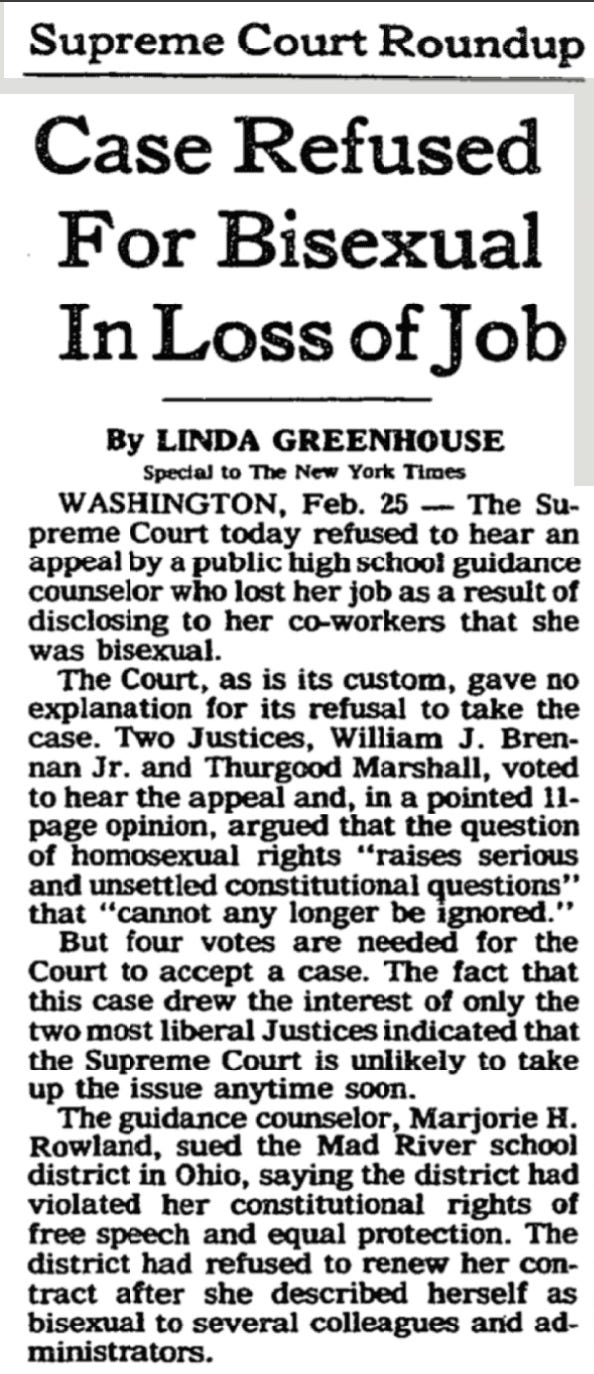

Each of these cases had been set in motion in 1972, just as the gay rights movement was gaining traction. Over the course of the decade, two lines of argument emerged, anchored in the First Amendment freedom of speech and the Fourteenth Amendment equal protection clauses. By the time the Supreme Court had its next opportunity to weigh in on the matter of employment rights for gay and lesbian teachers, Justice Brennan was fed up with the court’s persistent refusal to consider the important constitutional questions at stake. In 1985 he issued a dissent in Rowland v. Mad River Local School Dist. that would provide an important foundation for legal breakthroughs in the future.” (footnotes omitted).

The Supreme Court’s 1985 denial of certiorari and Justice William Brennan’s dissent appear below.

On petition for writ of certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

The petition for a writ of certiorari is denied.

Justice BRENNAN, with whom Justice MARSHALL joins, dissenting.

This case raises important constitutional questions regarding the rights of public employees to maintain and express their private sexual preferences. Petitioner, a public high school employee, “was fired because she was a homosexual who revealed her sexual preference-and, as the jury found, for no other reason.” 730 F.2d 444, 454 (CA6 1984) (Edwards, J., dissenting). Because the determination of the appropriate constitutional analysis to apply in such a case continues to puzzle lower courts and because this Court has never addressed the issues presented, I would grant certiorari and set this case for oral argument.

I

In December 1974, the petitioner was suspended from her nontenured position as a high school guidance counselor. In April 1975, the respondent School District acting through its School Board decided not to renew the petitioner's contract. A jury later made unchallenged findings that petitioner was suspended and not rehired solely because she was bisexual and had told her secretary and some fellow teachers that she was bisexual, and not for “any other reason.” The jury also found that the petitioner's mention of her bisexuality did not “in any way interfere with the proper performance of [her or other school staff members’] duties or with the regular operation of the school generally.” The jury concluded that the petitioner had suffered damages as a result of the decisions to suspend and not rehire her in the form of personal humiliation, mental anguish, and lost earnings.

The trial judge ruled that these findings supported petitioner's claims for violation of her constitutional right to free speech under Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968), and to equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. [note omitted] He therefore entered a judgment for damages for the petitioner.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed. The court first ruled that in light of our intervening decision in Connick v. Myers (1983), the decision to discharge petitioner based on her workplace statements was unobjectionable under the First Amendment because petitioner's speech was not about “a matter of public concern.” While accepting the jury's finding that petitioner's mention of her bisexuality had not interfered "in any way" with the "regular operation of the school," the court concluded that it was constitutionally permissible to dismiss petitioner "for talking about it.” Second, the court held that no equal protection claim could possibly have been made out, because there was presented "no evidence of how other employees with different sexual preferences were treated.” Without citation to any precedent, the court characterized the judgment for petitioner in the absence of such comparative evidence as “plain error.”

II

This case starkly presents issues of individual constitutional rights that have, as the dissent below noted, "swirled nationwide for many years.” (Edwards, J., dissenting). Petitioner did not lose her job because she disrupted the school environment or failed to perform her job. She was discharged merely because she is bisexual and revealed this fact to acquaintances at her workplace. These facts are rendered completely unambiguous by the jury's findings. Yet after a jury and the trial court which heard and evaluated the evidence rendered verdicts for the petitioner, the court below reversed based on a crabbed reading of our precedents and unexplained disregard of the jury and judge's factual findings. Because they are so patently erroneous, these maneuvers suggest only a desire to evade the central question: may a State dismiss a public employee based on her bisexual status alone? I respectfully dissent from the Court's decision not to give its plenary attention to this issue.

A.

That petitioner was discharged for her nondisruptive mention of her sexual preferences raises a substantial claim under the First Amendment. For at least 15 years, it has been settled that a State cannot condition public employment on a basis that infringes the employee's constitutionally protected interest in freedom of expression.” Nevertheless, Connick held that if “employee expression cannot be fairly considered as relating to any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community," disciplinary measures taken in response to such expression cannot be challenged under the First Amendment "absent the most unusual circumstances.” The court below ruled that Connick requires the conclusion that a bisexual public employee constitutionally may be dismissed for "talking about it." This conclusion does not result inevitably from Connick, and may be questioned on at least two grounds: first, because petitioner's speech did indeed "touch upon" a matter of public concern, and second, because speech even if characterized as private is entitled to constitutional protection when it does not in any way interfere with the employer's business.

Connick recognized that some issues are "inherently of public concern,” citing “racial discrimination” as one example. I think it is impossible not to note that a similar public debate is currently ongoing regarding the rights of homosexuals. The fact of petitioner's bisexuality, once spoken, necessarily and ineluctably involved her in that debate. Speech that “touches upon” this explosive issue is no less deserving of constitutional attention than speech relating to more widely condemned forms of discrimination.

Connick's reference to “matters of public concern” does not suggest a strict rule that an employee's first statement related to a volatile issue of public concern must go unprotected, simply because it is the first statement in the public debate. Such a rule would reduce public employees to second-class speakers, for they would be prohibited from speaking until and unless others first bring an issue to public attention. Cf. Egger v. Phillips, 710 F.2d 292, 317 (CA7 1983) (en banc) (“[T]he unpopularity of the issue surely does not mean that a voice crying out in the wilderness is entitled to less protection than a voice with a large, receptive audience”). It is the topic of the speech at issue, and not whether a debate on that topic is yet ongoing, that Connick directed federal courts to examine.

Moreover, even if petitioner’s speech did not so obviously touch upon a matter of public concern, there remains a substantial constitutional question, reserved in Connick, whether it lies “totally beyond the protection of the First Amendment” given its nondisruptive character. The recognized goal of the Pickering-Connick rationale is to seek a “balance” between the interest of public employees in speaking freely and that of public employers in operating their workplaces without disruption. As the jury below found, however, the latter interest simply is not implicated in this case. In such circumstances, Connick does not require that the former interest still receive no constitutional protection. Connick, and, indeed, all our precedents in this area, addressed discipline taken against employees for statements that arguably had some disruptive effect in the workplace. See, e.g., 461 U.S., at 151 (“mini-insurrection”); Mt. Healthy City Board of Ed. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274, 285, 575 (1977) (" dramatic and perhaps abrasive incident"); Pickering, supra, 391 U.S., at 569 (“critical statements”). This case, however, involves no critical statements, but rather an entirely harmless mention of a fact about petitioner that apparently triggered certain prejudices held by her supervisors. Cf. Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4-5 (1949). The Court carefully noted in Connick that it did "not deem it either appropriate or feasible to attempt to lay down a general standard against which all such statements may be judged.” This case poses the open question of whether nondisruptive speech ever can constitutionally serve as the basis for termination under the First Amendment.

B

Apart from the First Amendment, we have held that “[a] State cannot exclude a person from . . . any . . . occupation . . . for reasons that contravene the Due Process or Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232, 238-239 (1957). And in applying the Equal Protection Clause, “we have treated as presumptively invidious those classifications that disadvantage a ‘suspect class,’ or that impinge upon the exercise of a 'fundamental right.’” Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 216- 217 (1982); see also id., at 245 (BURGER, C.J., dissenting) (“The Equal Protection Clause protects against arbitrary and irrational classifications, and against invidious discrimination stemming from prejudice and hostility”). Under this rubric, discrimination against homosexuals or bisexuals based solely on their sexual preference raises significant constitutional questions under both prongs of our settled equal protection analysis.

First, homosexuals constitute a significant and insular minority of this country's population. Because of the immediate and severe opprobrium often manifested against homosexuals once so identified publicly, members of this group are particularly powerless to pursue their rights openly in the political arena. Moreover, homosexuals have historically been the object of pernicious and sustained hostility, and it is fair to say that discrimination against homosexuals is “likely . . . to reflect deep-seated prejudice rather than . . . rationality.” State action taken against members of such groups based simply on their status as members of the group traditionally has been subjected to strict, or at least heightened, scrutiny by this Court.

Second, discrimination based on sexual preference has been found by many courts to infringe various fundamental constitutional rights, such as the rights to privacy or freedom of expression. Infringement of such rights found to be “explicitly or implicitly guaranteed by the Constitution,” San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1, 33-34 (1973), likewise requires the State to demonstrate some compelling interest to survive strict judicial scrutiny. Plyler, supra, 457 U.S., at 217. I have previously noted that a multitude of our precedents support the view that public employees maintain, no less than all other citizens, a fundamental constitutional right to make “private choices involving family life and personal autonomy.” Whisenhunt v. Spradlin, 464 U.S. 965, 971, 408 (1983) (dissenting from denial of certiorari). Whether constitutional rights are infringed in sexual preference cases, and whether some compelling state interest can be advanced to permit their infringement, are important questions that this Court has never addressed, and which have left the lower courts in some disarray.

[. . .]

Finally, even if adverse state action based on homosexual conduct were held valid under the application of traditional equal protection principles, such approval would not answer the question, posed here, whether the mere nondisruptive expression of homosexual preference can pass muster even under a minimal rationality standard as the basis for discharge from public employment. This record plainly demonstrates that petitioner did not proselytize regarding her bisexuality, but rather that it became known simply in the course of her normal workday conversations.

The School District agreed to submit the issue of disruption to the jury, and the jury found that knowledge of the petitioner's non-heterosexual status did not interfere with the school’s operation “in any way.” I have serious doubts in light of that finding whether the result below can be upheld under any standard of equal protection review.

[note omitted]

III

The issues in this case are clearly presented. By reversing the jury's verdict, the Court of Appeals necessarily held that adverse state action taken against a public employee based solely on his or her expressed sexual preference is constitutional. Nothing in our precedents requires that result; indeed, we have never addressed the topic. Because petitioner’s case raises serious and unsettled constitutional questions relating to this issue of national importance, an issue that cannot any longer be ignored, I respectfully dissent from the decision to deny this petition for a writ of certiorari. [footnotes omitted]

Justice POWELL took no part in the consideration or decision of this petition.

Aftermath

Here again, what follows was excerpted, with permission, from Margaret A. Nash and Karen L. Graves, Mad River, Marjorie Rowland, and the Quest for LGBTQ Teachers’ Rights:

One group of teachers inspired by the new push came out on the fourth National Coming Out Day, in 1991. Twenty-one teachers in the Los Angeles Unified School District met at the headquarters building and announced in front of television cameras that they were gay. In California, 1991 was an important year to take such a stand as Governor Wilson had just vetoed a bill that would have banned job discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The same day that these teachers came out at the school district headquarters, a protest of the governor’s veto was held in Sacramento.

In some districts and in some regions of the country, teachers did not face harassment and in fact, found supportive communities. John Pikala, for instance, a public high school teacher in St. Paul, Minnesota, participated in a weekend retreat in Minneapolis for gay and lesbian educators in 1989. After the retreat, he came out to his principal and had no problem; he then came out to colleagues in his district. He became part of an activist group that built coalitions with other civil rights groups and put up a poster with pictures of famous gays and lesbians in his classroom that read, “Unfortunately, history has set the record a little too straight.” In 1990 he walked with a large contingent of teachers in the Minneapolis Gay Pride march, noting that the teachers “received the loudest cheers from onlookers.” Even so, he also received harassing phone calls, including one from a person who shouted, “You dirty homosexual! You’re going to hell! DIE!” But for Pikala, the “few negative or indifferent reactions do not count for much compared with the overwhelming acceptance and support I have experienced.”

In 1994 a high school history teacher in Missouri came out to his students during a lesson on the Holocaust, a pedagogical decision that thrust him into the glare of the national media. Rodney Wilson had established a reputation as an excellent teacher who worked to make the study of history relevant to his St. Louis students.

Rodney Wilson

Wilson recalls getting the message as a young man growing up in the 1970s: gay people could not become teachers. But scholarly integrity won out in his efforts to teach students to respect the historical record. Wilson’s simple statement that, had he been living in Nazi Germany, he would have been branded with the pink triangle, led to community uproar. Although Wilson was reprimanded for “inappropriate classroom behavior,” many colleagues stood by his side, and support from the local chapter of the NEA was strong. He kept his job. That same year, Wilson founded the first Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) chapter outside of Massachusetts and established LGBT History Month, endorsed by GLADD, the Human Rights Campaign, the National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce, and the NEA.

[. . .]

By the 1990s, some states had passed laws protecting employees from workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation. [. . . . Nonetheless, in subsequent years, the trend in the states was to avoid enacting laws that openly discriminated] against LGBTs. [Instead] states enacted laws for protecting people who have religious or moral objections to homosexuality. Between 1993 and 2015, twenty-one states passed statewide Religious Freedom Restoration Acts.

Related cases

303 Creative LLC v. Elenis (2023) (6-3, holding that the First Amendment prohibits Colorado from forcing a website designer to create expressive designs speaking messages with which the designer disagrees.)

Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) (6-3, holding that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects employees against discrimination because they are gay or transgender.)

Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights (2018) (7-2, holding that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission’s actions in assessing a cakeshop owner’s reasons for declining to make a cake for a same-sex couple’s wedding celebration violated the free exercise clause.)

Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000) (In a 5-4 opinion, the Court held that “applying New Jersey's public accommodations law to require the Boy Scouts to admit Dale violates the Boy Scouts' First Amendment right of expressive association.”)

Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston (1995) (Court held that state court order requiring private citizens who organize a parade to include a gay group expressing a message that the organizers do not wish to convey violates the First Amendment.)

Gay Lib v. University of Missouri, 558 F.2d 848 (8th Cir., 1977) (university refusal to recognize gay student groups held violative of First Amendment.)

Acanfora, in Aumiller v. University of Delaware, 434 F. Supp. 1273 (D. Del. 1977) (firing a professor for publicly disclosing his homosexuality held violative of the First Amendment.)

Additional resources

Karen Graves, “A Matter of Public Concern: The First Amendment and Equal Employment for LGBT Educators,” 58 History of Education Quarterly 453 (2018).

Stephen Elkind and Peter Kauffman, “Gay talk: Protecting free speech for public school teachers,” 43 Journal of Law and Education, 147 (2014).

Darren Lenard Hutchinson, “Accommodating Outness: Hurley, Free Speech, and Gay and Lesbian Equality,” Journal of Constitutional Law, 85 (1998).

2024-2025 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Cases decided

Villarreal v. Alaniz (Petition granted. Judgment vacated and case remanded for further consideration in light of Gonzalez v. Trevino, 602 U. S. ___ (2024) (per curiam))

Murphy v. Schmitt (“The petition for a writ of certiorari is granted. The judgment is vacated, and the case is remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit for further consideration in light of Gonzalez v. Trevino, 602 U. S. ___ (2024) (per curiam).”)

TikTok Inc. and ByteDance Ltd v. Garland (9-0: The challenged provisions of the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act do not violate petitioners’ First Amendment rights.)

Cases for next term

Pending petitions

Petitions denied

MacRae v. Mattos (Thomas, J., special opinion)

L.M. v. Town of Middleborough (Thomas, J. dissenting, Alito, J., dissenting)

No on E, San Franciscans Opposing the Affordable Care Housing Production Act, et al. v. Chiu

Emergency applications

Netchoice v. Fitch (emergency relief denied with Kavanaugh, J., concurring with separate opinion: “I concur in the Court’s denial of NetChoice’s application for interim relief because NetChoice has not sufficiently demonstrated that the balance of harms and equities favors it at this time. . . To be clear, NetChoice has, in my view, demonstrated that it is likely to succeed on the merits — namely, that enforcement of the Mississippi law would likely violate its members’ First Amendment rights under this Court’s precedents.”)

Yost v. Ohio Attorney General (Kavanaugh, J., “IT IS ORDERED that the March 14, 2025, order of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio, case No. 2:24-cv-1401, is hereby stayed pending further order of the undersigned order of the Court. It is further ordered that a response to the application be filed on or before Wednesday, April 16, 2025, by 5 p.m. (EDT).”)

Free speech-related

Mahmoud v. Taylor (argued April 22 / free exercise case: issue: Whether public schools burden parents’ religious exercise when they compel elementary school children to participate in instruction on gender and sexuality against their parents’ religious convictions and without notice or opportunity to opt out.)

Thompson v. United States (decided: 3-21-25/ 9-0 w special concurrences by Alito & Jackson) (interpretation of 18 U. S. C. §1014 re “false statements”)

Last scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE.