Paths to protests: Gloria Browne-Marshall’s revealing new book

First Amendment News 478

It may be that humanity has but one chance in a thousand of survival,

but I would not be human if I did not struggle for that one chance.

– Albert Camus

Protest. The word originates from the Latin protestari, meaning “to bring forth publicly,” and the word testari, meaning to “assert” (from testis, meaning “witness”). The word found animating constitutional currency in such Supreme Court opinions as 1943’s West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 1963’s Edwards v. South Carolina, and 1969’s Tinker v. Des Moines, among others.

And yet, the word has even more cultural meaning, as actually practiced, in a variety of ways — ranging from published poems to recorded songs to symbolic gestures to comedic routines to public art.

Beyond the bounds of Supreme Court opinions comes a new book by Professor Gloria J. Browne-Marshall, which shines a revealing light on 500 years of protest and resistance in U.S. history.

The book is aptly titled A Protest History of the United States.

Guided by impressive research and scholarly nuance, Browne-Marshall explores the history of protest movements and rebellion in the United States. She starts with indigenous peoples’ resistance to European colonization and continues through to today’s climate change demonstrations. Slave revolts, labor strikes, anti-war marches, women’s rights protests, anti-police violence demonstrations, LGBTQ rallies, and more also find learned expression between the covers of Browne-Marshall’s engaging narrative.

A Protest History of the United States comes at a challenging time — when courage has too often yielded to cowardice and compromise. Given that, its stirring lessons can serve as needed antidotes to the timidity that has afflicted everyone from college presidents to law firm partners, not to mention those in the media who have bowed to our current president’s arbitrary demands.

Aided by a bounty of legal documents, archival materials, government documents, secondary sources, and memoirs, this book gives spirited voice to those who spoke out against the mistreatment of others, themselves, and the environment. In this illuminating chronicle of marginalized people seeking justice, the social and personal value of protest is underscored time and again. Aspirations comingle with realism in ways that reveal how what was once deemed impossible came to become possible.

By that measure, protest, at its best, is a combination of romanticism and realism.

Informed and articulate, Professor Browne-Marshall’s work is also passionate. True to the spirit of protest, she pulls no punches, sugarcoats no history, and never apologizes for dissent in the service of democracy. Agree with her or not, this author, playwright, essayist, and racial justice activist is not shy when it comes to speaking out. While she is too civil to be boisterous and in your face, in print and practice, she knows how to deliver a commanding blow to those who trade in pap and prejudice.

A certain kind of MLK-like pragmatism is at work in her speeches and writings. That pragmatism is both oppositional and inspirational. “Effective protest,” she likes to say, “is not just against something, but you have to be moving toward something.”

Her “vision” mindset mirrors some of what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. so skillfully set out in his 1967 book Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

Read this book, open your mind, get over your silent gutlessness, and take heed of the author’s hope:

“I want [my readers] to be more respectful of the gains made by people who protested over many, many years. I want them to realize that they, too, can be protestors in large and small ways. And I want them to understand that we gained so much of what we take for granted through protest.”

Select quotes from A Protest History of the United States

“Protest matters. Protests have led to changes in political will and winds.”

“Protest to me is spiritual.”

“Protest is primal.”

“Silent people allow bad things to happen as they try to wait out the controversy — until it comes for them.”

“The world will be made better by those who refuse to be silent.”

“To live in the United States is to be as conflicted as this nation, embracing an uncomfortable quiet that at any moment will be broken by a war abroad or a police shooting at home.”

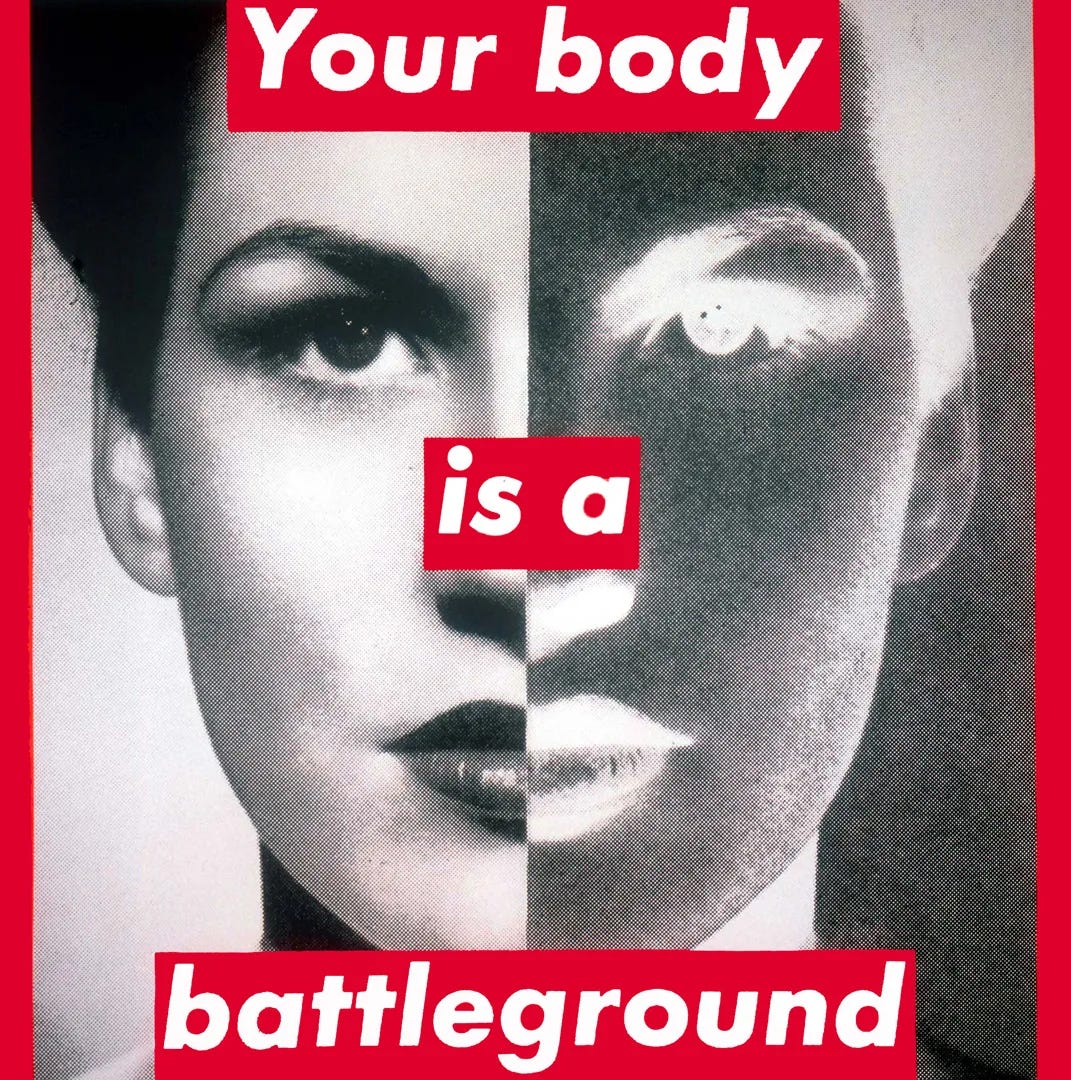

“The journey for women’s rights was a complex one based on not only gender but class, race, and religion. In the end, a woman’s body was the battlefield.”

“Protest has a spirit. There is something otherworldly about the bodies of strangers packed close together, chanting ‘No justice, no peace’ or ‘This is what democracy looks like.’”

Related

Later this week or next, our friends over at First Amendment Watch will post Susanna Granieri’s interview with Professor Browne-Marshall concerning her new book.

Lydialyle Gibson, “How to Protest Effectively,” Harvard Magazine (March 28)

New book by Lukianoff and Strossen

Greg Lukianoff and Nadine Strossen, The War On Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech—And Why They Fail, Heresy Press (July 22)

Heresy Press’s first non-fiction offering addresses free speech and creative freedom — central to the Press’s mission — through a systematic debunking of the most common pro-censorship arguments. Co-authored by Greg Lukianoff and Nadine Strossen, The War on Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech — And Why They Fail constitutes a bulwark against the persistent censorial efforts from both the political left and right.

At a time when conformist pressures threaten viewpoint diversity, and when political attacks on free expression are mounting, this book is a valuable resource for all who seek to understand and defend the right that is central to both individual liberty and our democratic self-government.

This concise volume is organized around 10 claims that proponents of speech restrictions regularly assert, such as: “words are violence,” “free speech is right-wing,” and “hate speech isn’t free speech.” In lively, clear, and persuasive prose, the authors examine the flaws in these pro-censorship assertions. The book also includes an insightful introduction by Jacob Mchangama, shedding additional light on the topic from historical and international perspectives.

Related

“What's Harvard's Problem with Free Speech?” Glenn Loury featuring Greg Lukianoff, The Glenn Show (July 12)

‘Only a very evil person would ask a question like that’

Sarah Ewall-Wice, “Trump Insults ‘Evil’ Reporter Who Dares to Ask About Flood,” The Daily Beast (July 11)

The exchange below between a CBS reporter and the President is indicative of how Trump relishes intimidating anyone who dares to ask tough questions. Yes, it’s his “right” to be a bully, and he exercises it with great delight. His my-way-or-no-way approach to presidential exchanges with the press (among others) only boosts runaway executive power at the cost of information vital to the public understanding of government actions.

As revealed in the excerpts below, when it comes to the critiques of his administration, President Trump prefers to attack the press rather than concede failure.

President Donald Trump lashed out at a reporter as ‘evil’ on Friday after she dared to ask him about the warnings given by the authorities before the deadly Texas floods.

[. . .]

When Trump opened the roundtable event up for questions, it did not go the way he wanted, and he immediately became defensive.

A reporter who identified herself as from CBS News in Texas asked the president about the lack of warning.

[. . .]

“Well, I think everyone did an incredible job under the circumstances,” Trump started, before tearing into the reporter.

“Only a bad person would ask a question like that, to be honest with you,” the president said. “I don’t know who you are, but only a very evil person would ask a question like that.”

Related

Michael S. Schmidt, “When Silence Speaks Volumes,” The New York Times (July 11)

Trailer: The Global Free Speech Summit 2025

The Future of Free Speech and Vanderbilt University are proud to present the second annual Global Free Speech Summit — a landmark event that explores the most urgent threats to free expression and offers bold solutions to protect this essential right.

Taking place on October 3-4 2025, the summit will bring together global voices for two days of critical dialogue.

Court enjoins contribution limit and disclosure provision

“Federal Judge Strikes Down Maine’s Question 1,” Institute for Free Speech (July 15)

In a major victory for free speech, a federal magistrate judge has blocked the campaign finance restrictions created by Maine’s “Question 1,” ruling that those restrictions violate fundamental constitutional rights.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Karen Frink Wolf granted a permanent injunction in the Institute for Free Speech case, Dinner Table Action, et al. v. Schneider, et al., preventing enforcement of the “Act to Limit Contributions to Political Action Committees That Make Independent Expenditures,” more commonly known as Question 1.

The law imposed a $5,000 annual limit on contributions to groups making independent expenditures and required disclosure of all donors regardless of contribution size. Previously, Maine had already agreed not to enforce the law while the litigation proceeded.

The Institute for Free Speech (IFS) and local counsel Joshua D. Dunlap of Pierce Atwood LLP filed the lawsuit, representing Dinner Table Action, For Our Future, and Alex Titcomb in challenging the measure.

New scholarly essay asserts ‘the fighting words doctrine lives’

“Fighting Words at the Founding,” Harvard Law Review (2025)

“God hates you wicked, baby-killing whores,” “cocksucker,” “fucking cunt,” and “shut your fucking mouth, you bitch” are statements that start fights. In 1791, it was similarly inflammatory to call someone a “drunkard,” “liar,” “puppy,” “blackguard,” “companion for negroes,” or (more ambitiously) a “cuckoldly knave.” Modern law labels speech that, in context, tends to provoke immediate violence “fighting words.” This kind of expression was proscribable in 1791 and is subject to content-based regulation today.

At the Founding, speakers of fighting words were indictable only if they intended to cause violence. Yet today, Americans who speak fighting words without any intention of causing a fight routinely face criminal sanctions. The Supreme Court has yet to rule definitively on whether the First Amendment requires that the government prove mens rea to punish the speaker of a fighting word. But in the lower courts, nearly every defendant prosecuted for speaking a fighting word faces strict liability: Her interior mental state is irrelevant. That approach breaks with the uniform practice of the common law at the time the nation ratified the First Amendment.

The difference matters. In 2001, Paul Graham was upset with the way police officers had detained a state fair attendee. After calling one of the officers a “bald-headed dick with ears,” he was arrested. In 1791, Graham could have argued his words merely “proceed[ed] from sudden heat and passion” and that he lacked intent to fight the policeman. That defense no longer exists, and Graham’s conviction stood on appeal. Just after noon in late 2009, a young man flashed a Sureño gang sign at a rival Norteño gang member. California indicted him for challenging the Norteño to a fight. In 1791, the defendant could have argued that he had not flashed the sign with intent to cause actual violence: He knew “there was a girl in the car” with the Norteño and figured “there won’t be a gang fight when [a] girl [is] present.” But today, that argument is worthless. The conviction was affirmed.

The fighting words doctrine lives. In Counterman v. Colorado, seven Justices joined opinions observing that the “Court has not upheld a conviction under the fighting-words doctrine in 80 years.” But the doctrine’s batting average at the Supreme Court is a poor proxy for its practical vitality; most fighting words cases get nowhere near trial, much less the nation’s apex tribunal. The doctrine is still good law. Armed with the power to punish insulting speech, prosecutors have descended on misguided and overzealous expression like bees on lavender.

Because the Supreme Court has yet to resolve the issue, the mens rea that the government must show to prosecute the speaker of a fighting word is an open question.

This Note argues that if the common law of 1791 is relevant to the scope of the First Amendment, it offers a single, simple rule: No speaker can be punished for a spoken fighting word unless he specifically intended to cause violence. Part I describes the proscribable categories, the constitutionally mandatory mens reas attached to them, and the uncertainty surrounding the mens rea for fighting words. Part II discusses the wrongful mental states attached to the eighteenth and early nineteenth-century regulations that would today fall within the fighting words doctrine. It finds that all plausible analogues required intent to cause violence.

More in the news

Eugene Volokh, “May Aliens Be Denied Lawful Permanent Resident Status Based on Their Speech?,” The Volokh Conspiracy (July 15)

Heather Price Ives, “Greene County staff permitted to speak to press after pushback from First Amendment groups,” The Daily Progress (July 15)

Brian Kerhin, “Taycheedah man challenges AI-generated child porn charges, cites First Amendment rights,” Fox11 News (July 15)

David Rubin, “Supreme Court case upholding age-verification for online adult content newly references ‘partially protected speech,’ gives it lesser First Amendment scrutiny,” FIRE (July 14)

David A. Graham, “Censorship for Citizenship,” The Atlantic (July 14)

“A Recap of the Trial Over the Trump Administration’s Crackdown on Pro-Palestinian Campus Protesters,” First Amendment Watch (July 14)

Susanna Granieri, “FIRE’s Robert Corn-Revere on Trump’s ‘Election Interference’ Suit Against Pollster,” First Amendment Watch (June 2)

2024-2025 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Cases decided

Firebaugh v. Garland (argued Jan. 10)

Villarreal v. Alaniz (Petition granted. Judgment vacated and case remanded for further consideration in light of Gonzalez v. Trevino, 602 U. S. ___ (2024) (per curiam))

Murphy v. Schmitt (“The petition for a writ of certiorari is granted. The judgment is vacated, and the case is remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit for further consideration in light of Gonzalez v. Trevino, 602 U. S. ___ (2024) (per curiam).”)

TikTok Inc. and ByteDance Ltd v. Garland (9-0: The challenged provisions of the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act do not violate petitioners’ First Amendment rights.)

Cases for next term

Pending petitions

Petitions denied

MacRae v. Mattos (Thomas, J., special opinion)

L.M. v. Town of Middleborough (Thomas, J. dissenting, Alito, J., dissenting)

No on E, San Franciscans Opposing the Affordable Care Housing Production Act, et al. v. Chiu

Emergency applications

Yost v. Ohio Attorney General (Kavanaugh, J., “IT IS ORDERED that the March 14, 2025 order of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio, case No. 2:24-cv-1401, is hereby stayed pending further order of the undersigned order of the Court. It is further ordered that a response to the application be filed on or before Wednesday, April 16, 2025, by 5 p.m. (EDT).”)

Free speech related

Mahmoud v. Taylor (argued April 22 / free exercise case: issue: Whether public schools burden parents’ religious exercise when they compel elementary school children to participate in instruction on gender and sexuality against their parents’ religious convictions and without notice or opportunity to opt out.)

Thompson v. United States (decided: 3-21-25/ 9-0 w special concurrences by Alito and Jackson) (interpretation of 18 U. S. C. §1014 re “false statements”)

Last scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE.