Take heed! Holmes’ much forgotten dissent in Baltzer v. United States

First Amendment News 496

It is better for those who have unquestioned and almost unlimited power in their hands to err on the side of freedom. We have enjoyed so much freedom for so long that perhaps we are in danger of forgetting that the Bill of Rights, which cost so much blood to establish, still is worth fighting for, and that no title of it should be abridged.

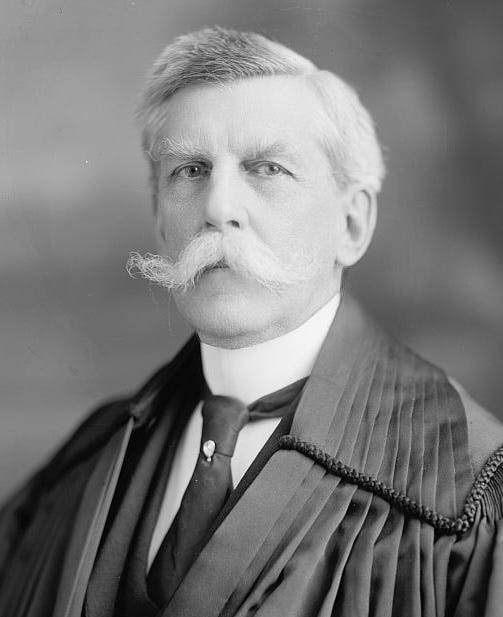

— Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., dissenting in Baltzer v. United States

Read those words, and then again. Ponder them; it will serve you well. After all, it seems that nearly every day there is some new and high-handed executive use of “almost unlimited power” — the Constitution and Bill of Rights be damned. Too many (from cabinet officials to members of Congress) remain cowardly silent to the “dangers” of such abhorrent abridgments of free expression, due process, and the rule of law.

Sometimes a sobering smack of old words, cast in modern times, can help to move the mind, if only a bit. On that score, Justice Holmes is called to the stand as an expert witness for the defense of our constitutional democracy.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was 77 when he penned the words quoted above. He had been an Associate Justice for 16 years. The “Yankee from Olympus,” as Catherine Drinker Bowen once tagged him, had yet to compose his landmark free speech opinions in 1919’s Schenck v. United States and what followed. Still, there was a window into them in his unpublished dissent in Baltzer v. United States. As Sheldon Novick put it: “This was Holmes at his best.”

Holmes was gravely aware of the “cost of so much blood.” Fifty-six years earlier, he had been shot through the neck and wounded at the battle of Antietam Creek. Those costs were to be paid once again; the Nation had entered the war the year before. In that storm of conflict, President Woodrow Wilson aggressively hurled his political might behind the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.

It is in that context that Holmes urged those who exercise “unquestioned and almost unlimited power” to do so with caution, so that they might “err on the side of freedom.”

Yesterday’s admonition is well-suited to be today’s cautionary counsel.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time Holmes’ unpublished dissent has been made available online, sans any firewall. A print version of the opinion, replete with commentary, can be found in pages 215-219 of The Fundamental Holmes: A Free Speech Chronicle and Reader (Cambridge University Press, 2010), which I edited.

248 U.S. 593 (1918)

Case No.: 320

Vote: 7–2 (per curiam)

Argued: Late November 1918

Holmes’ dissent distributed: December 3, 1918

Government concedes error: December 16, 1918

For petitioner: Mr. Joe Kirby

For respondent: Mr. William C. Rempfer

Emanuel Baltzer and William J. Head were farmers in Hutchinson County, South Dakota. After the United States entered World War I, it, along with twenty-six others, formed an organization known as a “German Socialist local,” and sent a petition “of an intimidating nature” to Governor Peter Norbeck of South Dakota. In the petition, they objected to the draft law quotas, criticized the war, and asked the governor to renounce the war. Though the petition was not circulated publicly, they were nonetheless convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917.

The plaintiffs in error appealed the ruling against them in the District Court for the United States for the District of South Dakota. Baltzer was the first such case involving a First Amendment right-of-petition claim to be heard by the Supreme Court. Although a majority was initially prepared to rule against the petitioners, no such opinion was ever rendered. Instead, the Justices granted the motion of the Solicitor General, who had confessed error. The Court then reversed and remanded the case. Before doing so, however, Holmes had prepared a dissent, which Brandeis planned to join.

In this regard, Sheldon Novick made some telling observations:

Holmes’s dissent was so disturbing in its attack on the majority, at a time when they feared growing civil unrest, that Chief Justice Edward Douglass White asked the Court to delay issuing any decision; and the Justice Department, apparently having learned of the dissent-perhaps from the Chief Justice or Brandeis, who was close to President Wilson, confessed error and withdrew. The following month, White assigned the opinion in Schenck to Holmes, in the hope of securing a unanimous Court, albeit a more moderate one.

Holmes’s dissent was never officially published and became publicly available only in 1991, though it was seldom noticed. (See Sheldon M. Novick, “The Unrevised Holmes and Freedom of Expression,” 1991 Supreme Court Review 301, 388-90).

Holmes’s dissent follows:

The only evidence against the plaintiffs in error is that the petition set forth in the indictment was signed and sent by them to the Governor of the State, and to two other officials probably supposed to have power. It was not circulated publicly. The signing and sending of it is taken to amount to willfully obstructing the recruitment and enlistment service of the United States. Uniting to sign and send it is supposed to amount to a conspiracy to do the same thing and also to a conspiracy to prevent the Governor by intimidation from discharging his duties as an officer of the United States in determining the quota of men to be furnished for the draft by the local board. I can see none of these things in the document. It assumes that the draft is to take place and complains that volunteers have been counted with the result that counties have been exempted. It demands that the Governor should stand for a referendum on the draft and advocates the notion that no more expense should be incurred for the war than could be paid in cash and that war debts should be repudiated. It demands an answer and action or resignation on penalty of defeat at the polls of himself and “your little nation J. P. Morgan.” The latter phrase was explained by the writer to mean J. P. Morgan’s class, as I think it obviously does without explanation. The class is supposed to stand behind the Governor and to be destined to defeat with him if he does not do as he is asked.

It seems to me that this petition to an official by ignorant persons who suppose him to possess power of revision and change that he does not, and demand of him as the price of votes, of course assumed to be sufficient to turn the next election, that he make these changes, was nothing in the world but the foolish exercise of a right. I cannot see how asking a change in the mode of administering the draft so as to make it accord with what is supposed to be required by law can be said to obstruct it. I cannot see how combining to do it is conspiracy to do anything that citizens have not a perfect right to do. It is apparent on the face of the paper that it assumes the power to be in the person addressed. I should have supposed that an article in a newspaper advocating these same things would have left untouched the sensibilities even of those most afraid of free speech. As to the repudiation of the war debt that obviously was a statement of policy not something contemplated as happening forthwith by the fiat of the Governor. From beginning to end the changes advocated are changes by law, not in resistance to it, the only threat being that which every citizen may utter, that if his wishes are not followed his vote will be lost.

The petition purported to come from members of the Socialist party all bearing German names. But those facts were not of themselves evidence of an attempt to obstruct. On the other hand they gave notice of probable bias on the part of the writers that would be likely to be appreciated by the world at large. I do not see that the case can be strengthened by argument if the statement of the fact does not convince by itself.

Real obstructions of the law, giving real aid and comfort to the enemy, I should have been glad to see punished more summarily and severely than they sometimes were. But I think that our intention to put out all our powers in aid of success in war should not hurry us into intolerance of opinions and speech that could not be imagined to do harm, although opposed to our own. It is better for those who have unquestioned and almost unlimited power in their hands to err on the side of freedom. We have enjoyed so much freedom for so long that perhaps we are in danger of forgetting that the bill of rights which cost so much blood to establish still is worth fighting for, and that no title of it should be abridged. I agree that freedom of speech is not abridged unconstitutionally in those cases of subsequent punishment with which this court has had to deal from time to time. But the emergency would have to be very great before I could be persuaded that an appeal for political action through legal channels, addressed to those supposed to have power to take such action was an act that the Constitution did not protect as well after as before.

New book on Herndon v. Lowry (1937)

Brad Snyder, “You Can’t Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads: Angelo Herndon’s Fight for Free Speech,” (W.W. Norton, 2025)

The story of a young, Black Communist Party organizer wrongly convicted of attempting to incite insurrection and the landmark case that made him a civil rights hero.

Decades before the impeachment of an American president for a similar offense, Angelo Herndon was charged under Georgia law with “attempting to incite insurrection” ― a crime punishable by death. In 1932, the eighteen-year-old Black Communist Party organizer was arrested and had his room illegally searched and his radical literature seized. Charged under an old slave insurrection statute, Herndon was convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to eighteen to twenty years on a chain gang. You Can’t Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads chronicles Herndon’s five-year quest for freedom during a time when Blacks, white liberals, and the radical left joined forces to define the nation’s commitment to civil rights and civil liberties.

Herndon’s champions included the young, Black Harvard Law School-educated attorney Benjamin J. Davis Jr.; the future historian C. Vann Woodward, who joined the interracial Herndon defense committee; the white-shoe New York lawyer Whitney North Seymour, who argued Herndon’s appeals; and literary friends Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, and Richard Wright. With their support, Herndon won his freedom and reinvented himself as a Harlem literary star until a dramatic fall from grace.

A legal odyssey of Herndon’s narrow escape from certain death because of his unpopular political beliefs, You Can’t Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads explores Herndon’s journey from Alabama coal miner to Communist Party organizer to Harlem hero and beyond. Brad Snyder tells the stories of the diverse coalition of people who rallied to his cause and who twice appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. They forced the Court to recognize free speech and peaceable assembly as essential rights in a democracy ― a landmark decision in 1930s America as well as today.

Forthcoming book on Island Trees v. Pico

Anthony Aycock, “Just Plain Filthy: The Story Behind Book Banning’s Trial of the Century,” Bloomsbury Libraries (June 11, 2026)

With the threat to intellectual freedom increasing around the country, this book takes a look at the first ever school book ban case to be decided by the high courts, and offers insights into how we can use history to help the future.

In 1975, the school board members of a small Long Island town did what they thought was a no-brainer: they ordered the removal of nine books from a high school library. The books included some classics — Richard Wright’s Black Boy; Desmond Morris’s The Naked Ape; Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five — but that didn’t matter to board chair Richard Ahrens, who called the collection “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy.” Maybe he thought the town was with him. Maybe he thought nobody would care. He certainly didn’t think he would be sued by seventeen-year-old Steven Pico or that the case would end up before the United States Supreme Court, the first and only book ban dispute ever to do so.

The only one so far. Recent years have seen a surge in book challenges, and it is only a matter of time before another reaches the high court. Island Trees v. Pico ended in a loss for the school board, but not a resounding one. It left enough daylight for the current justices to reach a different conclusion. What was the court’s ruling? How did it come about? What was the book ban climate in the 1970s and 80s, and how did it differ from today’s? Just Plain Filthy is the first book to tell the complete story of Island Trees v. Pico, the flawed, fascinating case that is the cornerstone of intellectual freedom in America. For now.

New scholarly article on First Amendment exceptions to valid laws

Richard H. Fallon, Jr., “First Amendment Exceptions to Otherwise Valid Laws: A Doctrinal and Meta-Doctrinal Perspective,” Northwestern University Law Review (2025)

When do the First Amendment’s Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses require exceptions to generally valid laws? Recently, the Supreme Court has upheld a number of such exceptions, which excuse some speakers and religiously motivated actors from legal duties that apply to others, including in prominent cases under antidiscrimination statutes and emergency pandemic regulations. By contrast, other landmark cases–such as United States v. O’Brien and Employment Division v. Smith — insist that First Amendment exceptions should be rare.

In analyzing the fraught and confusing issues that surround First Amendment exceptions, this Article makes four main contributions. First, it conceptualizes claims to First Amendment exceptions as as-applied challenges, which the Supreme Court purports to welcome in other contexts, and elucidates the role of “severability” principles in making as-applied challenges possible. Insofar as as-applied challenges are unavailable, the Article argues, applicable doctrine necessarily relies on facial challenges to protect First Amendment rights. Second, the Article conducts a doctrinal survey of judicially mandated exceptions under both the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses and highlights the diverse variety of tests that determine when claims to exceptions can succeed.

The survey confirms that First Amendment exceptions are indeed exceptional, though not anomalous. It additionally establishes, however, that facial challenges are the more common mechanism for protecting First Amendment rights–a conclusion contrary to the Supreme Court’s frequent admonition that facial challenges should be rare and disfavored. Third, the Article probes beneath the surface of current doctrines authorizing First Amendment exceptions and generates insights about the nature of First Amendment rights and the diverse interests that those rights protect.

Based on variance in the Supreme Court’s receptivity to claims to First Amendment exceptions, the Article draws provocative conclusions about which underlying interests the Justices view as more and less deserving of judicial protection. Fourth, the Article exposes flaws in the Supreme Court’s reasoning in designing and applying frameworks authorizing First Amendment exceptions in two recent leading cases, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis under the Free Speech Clause and Tandon v. Newsom under the Free Exercise Clause. Overall, the Article enriches previous understandings of how exceptions do and should fit into a complex ecosystem of First Amendment rights and interests

Forthcoming scholarly article on facial recognition technology and the First Amendment

Joseph A. Tomain, “Facial Recognition Technology and the First Amendment,” Michigan Technology Law Review (2026)

The growing ubiquity of facial recognition technology (FRT) is a problem. While much has been written on harmful government use of FRT, little has been written regarding harmful private actor use. This Article helps fill a gap in the literature by providing a detailed analysis of the First Amendment interests at stake when private actors use FRT. Specifically, this Article analyzes whether laws that limit the use of publicly available photographs to create faceprints for inclusion in FRT databases violate the First Amendment rights of private actors.

In May 2025, a multidistrict litigation against Clearview AI, an FRT company, offered an opportunity to answer that question, but it settled. The court stated that the “settlement agreement leaves unresolved the question that motivated this multidistrict litigation: whether the collection of publicly available biometric information for use by private or government entities . . . is reconcilable with constitutional privacy rights.” This Article helps answer that unresolved question. But privacy is too narrow a framework. Constitutional rights of free speech, association and assembly are also affected.

This Article makes two claims, one descriptive and one normative. The descriptive claim is two-fold: (1) existing First Amendment law does not resolve the novel question of whether laws that limit how private actors use publicly available images violate their First Amendment rights, and (2) free speech advocates are divided on the proper response. The normative claim answers the unresolved question by concluding that some regulation of private actor use of publicly available images to create faceprints and FRT databases should be found constitutionally permissible.

Not only does this Article analyze the First Amendment arguments of FRT companies like Clearview AI, but it also introduces the other half of the story: the First Amendment interests of the faceprinted. After identifying problematic uses of FRT and showing the inadequacy of existing law, this Article makes the normative argument by engaging with three methods of constitutional interpretation, identifying First Amendment values that support regulating the use of FRT, and drawing lessons from Fourth Amendment doctrine and theory.

Related: AI lawsuits

Dave Collins, Matt O’Brien, and Barbara Ortutay, “Open AI, Microsoft face lawsuit over ChatGPT’s alleged role in Connecticut murder-suicide,” ABC News (Dec. 11)

Will Steakin, “Lawsuit alleges ChatGPT convinced user he could ‘bend time,’ leading to psychosis,” ABC News (Nov. 7)

Floyd Abrams on ‘How Unique is the First Amendment?’

“2025 Christiane Amanpour Lecture: How Unique is the First Amendment?” URI Harrington School of Communication and Media (Nov. 3, 2025)

Institute For Free Speech exchange on ‘gender ideology’ and free speech

“Speech Under Fire: How Gender Ideology Threatens Free Speech,” Institute for Free Speech (Nov. 24, 2025)

Sex-based rights activists Glenna Goldis and Kara Dansky join IFS Senior Attorney Del Kolde to discuss how gender ideology threatens free speech. IFS Senior Attorney Brett Nolan moderates the discussion.

More in the news

“Somali Flag Flown Outside Vermont School Building Over Trump ‘Garbage’ Slur Brings Threats,” First Amendment Watch (Dec. 15)

Byron Tau, “How a Calif. AM radio station struggles under Trump administration’s assault on news media,” Free Speech Center (Dec. 15)

Graham Piro, “Texas runs afoul of the First Amendment with new limits on faculty course materials,” FIRE (Dec. 12)

“California Colleges Settle Antisemitism Complaints With Jewish Groups and Individuals,” First Amendment Watch (Dec. 12)

D.D. Degg, “Cartoon Facebook Page Wins First Amendment Lawsuit,” The Daily Cartoonist (Dec. 12)

“FIRE statement on Trump demand for social media history of foreign tourist,” FIRE (Dec. 10)

Marc Tamasco, “Jane Fonda says Warner Bros. Discovery sale ‘threatens’ the First Amendment, warns Trump will take advantage,” Fox News (Dec. 6)

Liam Scott, “The SLAPP Problem Is Worse Than We Thought,” Columbia Journalism Review (Dec. 4)

“From The Joke Files: A Comedy and Censorship Roundtable,” ACLU (Nov. 17)

2025-2026 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

Chiles v. Salazar (argued: Oct. 7)

Olivier v. Brandon (argued: Dec. 3)

First Choice Women’s Resource Centers, Inc. v. Platkin (argued: Dec. 2)

National Republican Senatorial Committee v. Federal Election Commission (argued: Dec. 9)

Pending petitions

360 Virtual Drone Services LLC v Ritter

Emergency docket (‘Shadow docket’)

Margolin v. National Association of Immigration Judges (application for a stay)

Chamber of Commerce v. Sanchez (application withdrawn)

Petitions denied

Cambridge Christian School, Inc. v. Florida High School Athletic Association, Inc.

Hartzell v. Marana Unified School District

Evans Hotels, LLC v. Unite Here! Local 30

Last Scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of FIRE.