Book ban mania: New documentary and legal challenges contest censorship

First Amendment News 489

According to a new report from PEN America, public schools across the U.S. saw more than 6,800 book bans across 23 states and 87 public school districts during the 2024-25 school year

[It is] beyond dispute that schools and school boards must operate within the confines of the First Amendment.

The danger

On Aug. 24, 1814, during the War of 1812, the British torched the national library and its 3,000 books. “The following year, Congress purchased the 6,487-volume library of former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson to replace the lost collection.”

The British attack on books was an act of war. When Anthony Comstock came along, the war continued but on a different, ruthless plane — the war of Victorian morality as codified in the Comstock Act of 1873 (see Robert Corn-Revere, The Mind of the Censor and the Eye of the Beholder (2021)).

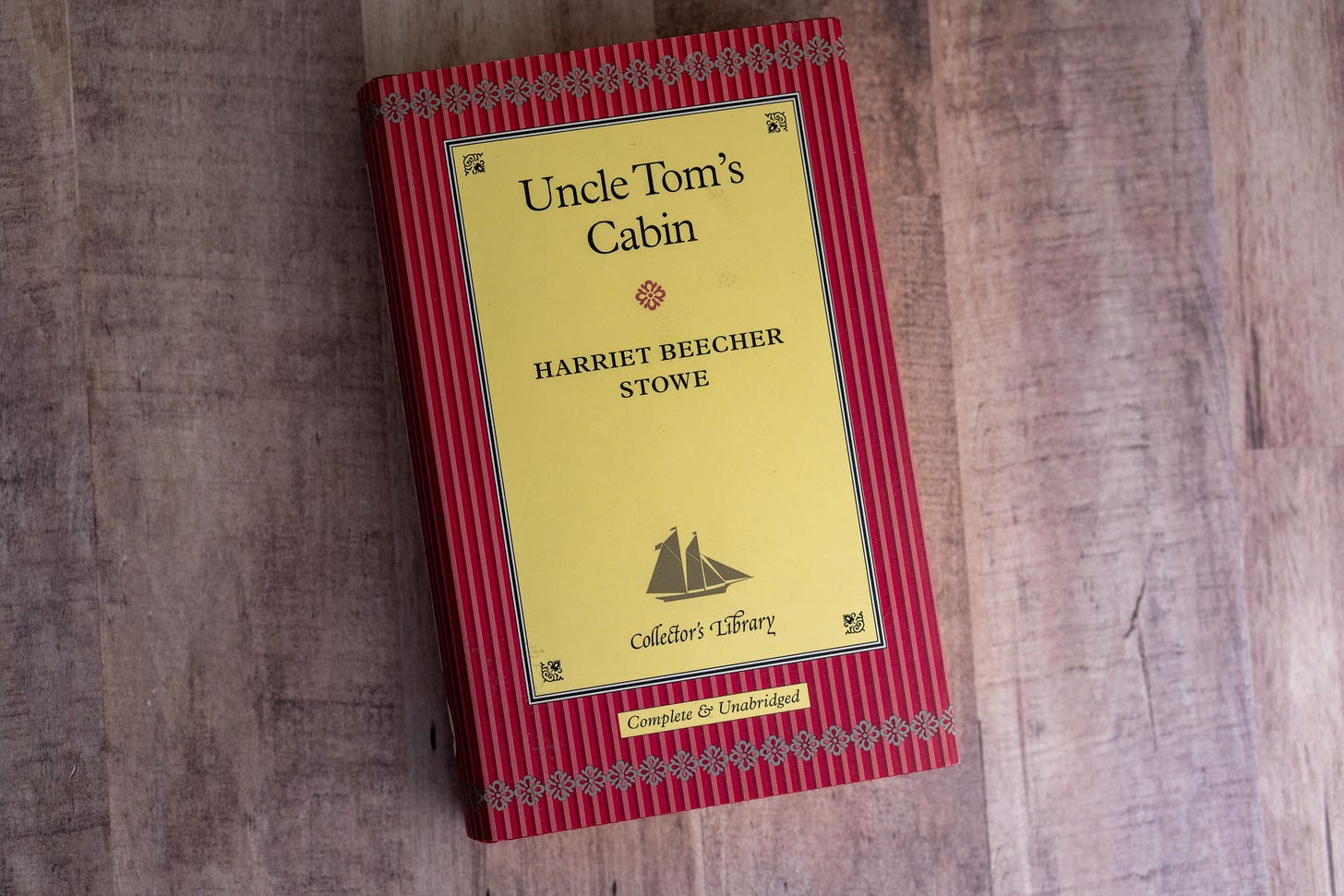

In ways that foreshadowed the present state of affairs under a recent Trump Executive Order (see also FAN 483), Southern Jim Crow-era campaigns were also launched by the

United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and others to ensure that school textbooks contained sympathetic portrayals of the South’s role in the Civil War. Of course, by that censorial measure, books like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) became prime candidates for book banning.

Related

Ishena Robinson, “The History They Don’t Want You to Know” (Legal Defense Fund, Feb. 25, 2023):

[The UDC] launched a campaign beginning in the early 1900s as part of the backlash to Reconstruction to promote a revisionist telling of the Civil War that downplayed the horrors and evils of slavery, while falsely glorifying the Confederacy as a last redoubt of a supposedly better, pre-industrial age.

The UDC flooded public schools in the South with history textbooks written from the deliberately warped and white supremacist perspective that the war was rooted in northern states’ aggression against the economic rights of southern slave owners. Instead of depicting these slaveholders as the eager proponents of racist terror that they were, this narrative suggested they were benevolent to the Black people they dehumanized, brutalized, exploited, assaulted, and killed. The role of Black people’s labor in the South’s flourishing economy was minimized or outright erased in these school texts. The UDC successfully shaped school curricula in the service of this narrative, and untold numbers of students were taught well into the 20th century that institutionalized racism was justified.

The lesson

Burning books or banning them constitutes a war against the minds of men and women. It is a way of cutting off informational oxygen until one suffocates under the pressure of ignorance. By James Madison’s libertarian measure, libraries were essential to promote “the advancement and diffusion of Knowledge, which is the only Guardian of true liberty.” (June 30, 1825 letter to George Thompson). Public libraries were not created to appease parochial biases, be they conservative or liberal, religious or nonreligious, or whatever the prevailing orthodoxy.

Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

— Library Bill of Rights (1939, sect. II)

In her book Foundations of Intellectual Freedom (American Library Association, 2022), Emily Knox identified four kinds of book censorship:

Removal: abolishing certain books from the library, classroom, or bookstore shelves;

Relocation: moving the specific books to harder-to-access locations within the library, such as creating an “adults only” section;

Restriction: limiting access to books or keeping a book in an inaccessible place unless someone gets special permission to view it; and

Redaction: striking through or covering sections of materials so they cannot be seen by readers.

Those “Four Rs” of censorship explain both the method and the problem with abridging knowledge.

Related

Mead Gruver, “Wyoming library director fired amid book dispute wins $700,000 settlement,” Free Speech Center (Oct. 13)

New documentary: ‘The Librarians’

“The Librarians” directed by Kim A. Snyder

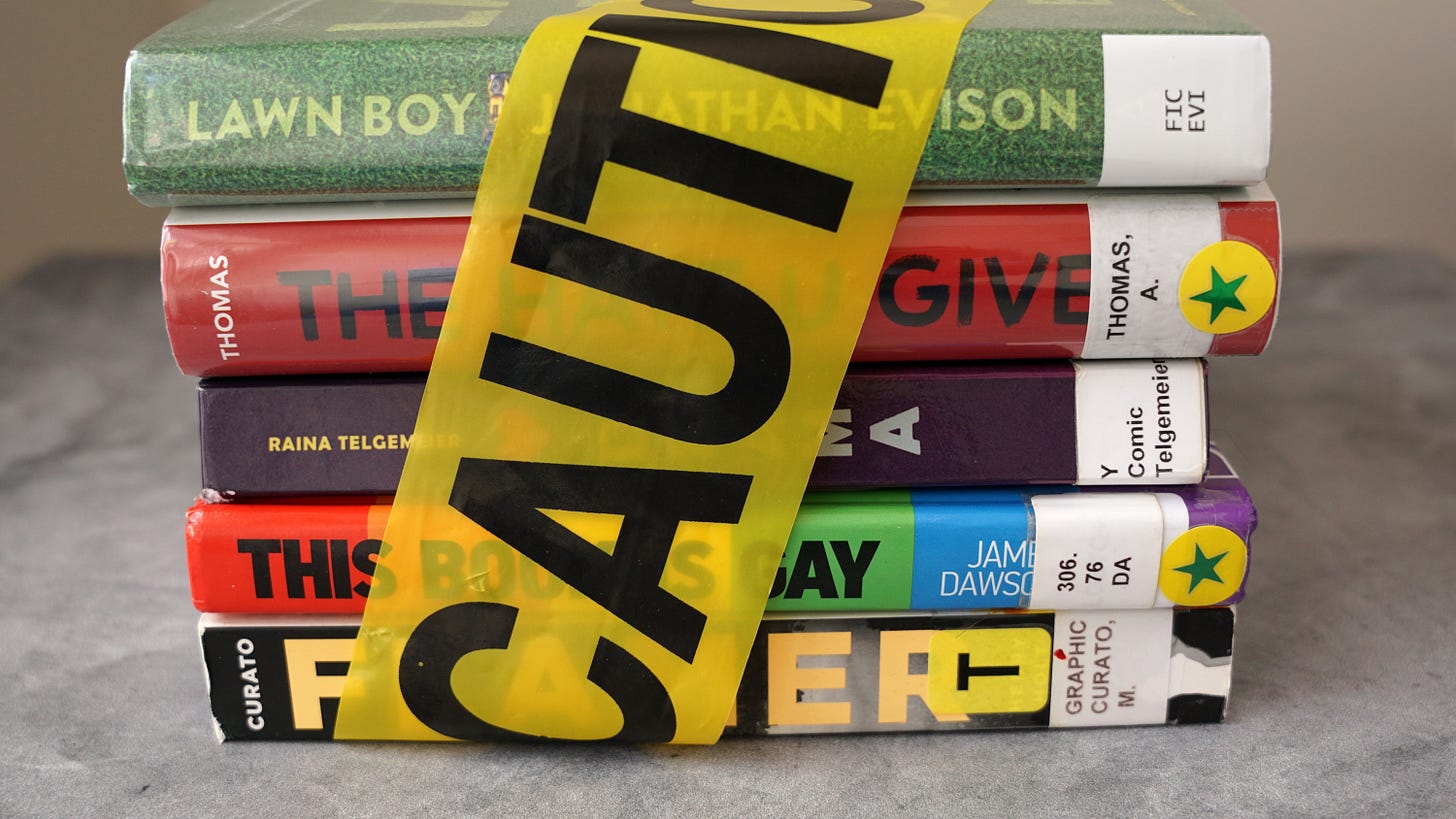

In Texas, the Krause List targets 850 books focused on race and LGBTQIA+ stories — triggering sweeping book bans across the U.S. at an unprecedented rate. As tensions escalate, librarians connect the dots from heated school and library board meetings nationwide to lay bare the underpinnings of extremism fueling the censorship efforts. Despite facing harassment, threats, and laws aimed at criminalizing their work — the librarians’ rallying cry for freedom to read is a chilling cautionary tale.

Related

John Yang and Laine Immell, “The fight against book bans by public school librarians shown in new documentary,” PBS News (Oct. 5, 2025)

“Project 2025 and Its Consequences for Libraries, Every Library Institute,” July 2024

“Delaware ACLU releases ‘Guide to the First Amendment for LGBTQ+ Youth’,” FAN 355 (Nov. 11, 2022)

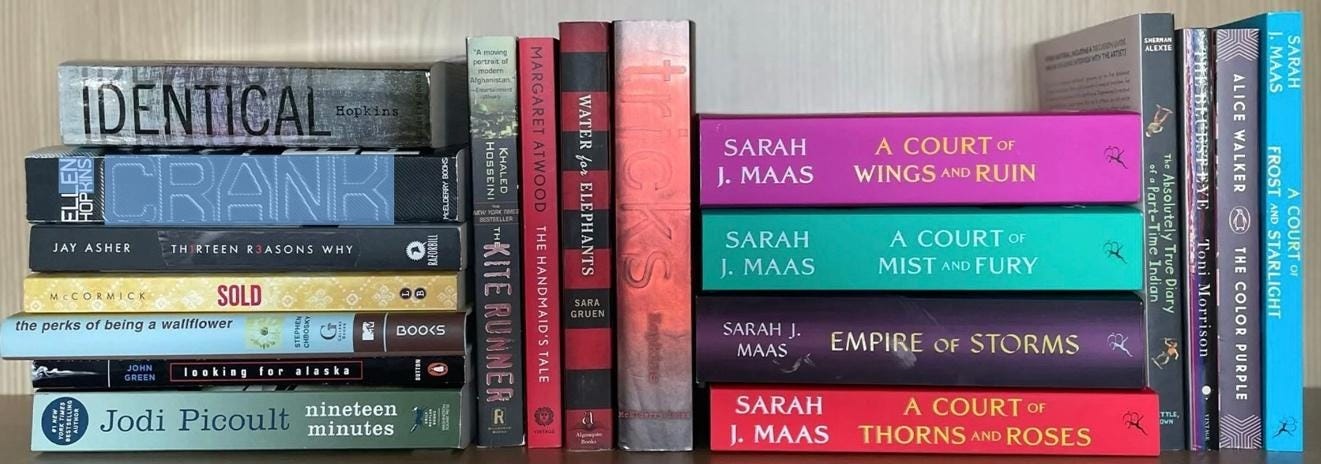

Most Banned Books of the 2024-2025 School Year (PEN America)

Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Jennifer Niven, Breathless and Patricia McCormick, Sold

Malinda Lo, Last Night at the Telegraph Club

Sarah J. Maas, A Court of Mist and Fury

Ellen Hopkins, Crank and Judy Blume, Forever and Stephen Chbosky, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, and Gregory Maguire, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

George M. Johnson, All Boys Aren’t Blue, and Sarah J. Maas, A Court of Thorns and Roses, and Elana K. Arnold, Damsel, and Kody Keplinger, The DUFF: Designated Ugly Fat Friend, and Jodi Picoult, Nineteen Minutes, and Jennifer L. Armentrout, Storm and Fury.

Related

“The Normalization of Book Banning,” PEN America (Oct. 1)

Books on book bans

Christina Ellis, Renee Ellis, Edha Gupta, Ben Hodge, Patricia Jackson, and Olivia Pituch, Ban This!: How One School Fought Two Book Bans and Won (and How You Can Too), Zest Books (2025)

Kirsten Miller, Lula Dean’s Little Library of Banned Books: When Banned Books Shake Up a Small Georgia Town―A Funny and Poignant Novel about Censorship, Friendship, and Unexpected Connections, William Morrow (2025)

Sally McGraw, Book Bans: Reading Under Siege, Lerner Publishing Group (2025)

Herbert N. Foerstel, Banned in the U.S.A. A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries, Greenwood (2nd ed., 2002)

Nicholas J. Karolides, Margaret Bald, and Dawn B. Sova, 100 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature, Checkmark Books (1999)

Cert. petition, re: Texas county library book ban

The issue: At the urging of a handful of private citizens, government officials in Llano County, Texas, removed seventeen books from the county library’s shelves. A district court found that those book-removal decision were motivated by a desire to censor particular viewpoints. The question presented is: Whether those book-removal decisions are subject to scrutiny under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

Summary of arguments

This case presents a critically important First Amendment question that has divided the circuits. In recent years, state and local governments have increasingly removed books from public libraries because they disagree with the ideas those books promote. Here, for instance, the public library in Llano County, Texas, removed books — including publicly acclaimed nonfiction works and memoirs — because they espoused ideas about racial justice and gender identity that government officials deemed “inappropriate.” Such a viewpoint-based book ban violates the “bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment”: “the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.” Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 414 (1989).

The issue in this case is whether the First Amendment has any application to such censorship. For more than forty years, dating back to this Court’s decision in Board of Education v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982), the answer was yes. In Pico, no opinion garnered a majority of the Court, but eight Justices agreed that First Amendment scrutiny applies to a school library’s removal of books for the purpose of suppressing particular viewpoints.

[. . .]

Following Pico, lower courts coalesced around the position that school and public libraries had substantial discretion to remove books but were barred from doing so to pursue viewpoint-discriminatory aims. In this case, the en banc Fifth Circuit broke from that precedent. A majority of the court held that patrons of the Llano County Public Library had no First Amendment right to challenge the library’s removal of books—even for openly viewpoint-discriminatory reasons. And a plurality deemed the library’s book-removal decisions to be government speech. Under both rationales, the consequence is the same: public libraries’ book-removal decisions are entirely immune from Free Speech Clause scrutiny. Indeed, respondents’ counsel conceded that respondents’ position has no “limiting principle” and would allow a public library to, for instance, remove all books touting “the benefits of firearms ownership” or “the dangers of communism.” Pet. App. 102a-103a & n.16 (Higginson, J., dissenting).

Little v. Llano County (5th Cir., 2025) (The ACLU filed an amicus brief as did FIRE // FIRE most recently filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court).

Related book-ban cases in lower courts

Fayetteville Public Library, et al. v. Todd Murray, et al. (8th Cir. 2025) (challenging Arkansas’s broad attempt to regulate libraries and bookstores under Act 372. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit was asked to uphold a district court ruling striking down Act 372 as unconstitutional. Arkansas’ sweeping law grants anyone the authority to demand that books be removed or locked away in “adults-only” sections, and threatens librarians and booksellers with up to a year in jail simply for providing minors access to constitutionally protected works.) (see FIRE’s amicus brief here)

Related 2025 Supreme Court case

Mahmoud v. Taylor (6-3 per Alito, J., holding that parents challenging the Montgomery County Board of Education’s introduction of certain “LGBTQ+-inclusive” storybooks, along with the board’s decision to withhold parental opt-outs from that instruction, are entitled to a preliminary injunction)

Delaware passes ‘Freedom to Read Act’

“Governor Matt Meyer Signs Pro-Free Speech Legislation,” Delaware.gov. (Sept. 15)

Governor Matt Meyer signed two bills, Senate Bill 80 and House Bill 119, strengthening free speech protections in Delaware and ensuring free access to books and other library materials in public and school libraries.

“Freedom of expression and access to diverse ideas are the bedrock of a strong democracy,” said Governor Matt Meyer. “These bills protect Delawareans’ voices — whether it’s standing up to powerful interests or ensuring our libraries remain places where every child can explore, learn, and see themselves reflected in the stories they read. These laws will help us raise a generation of critical thinkers and empathetic leaders, because our communities are stronger when we engage with ideas, not erase them.”

House Bill 119, sponsored by Rep. Krista Griffith and Sen. Elizabeth “Tizzy” Lockman, ensures that books and resources cannot be removed or banned from public and school libraries based on the author’s background or because of partisan, ideological, or religious objections. The bill also sets up a clear, fair process for reviewing complaints about library materials, keeping items under review available until that review is complete. Similarly, school libraries must follow a uniform objection process with clear timelines, keeping materials accessible during review. Appeals to review decisions can be made to a new statewide School Library Review Committee created by this bill.

“Libraries have always been a place where everyone, regardless of age, background, or belief, can freely explore ideas and access information. Unfortunately, over the past several years, we’ve seen a rise in attempts to remove books and censor content nationally simply because they present perspectives that some may disagree with,” said Rep. Krista Griffith. “The Freedom to Read Act is a balanced approach that allows community members to raise concerns through a clear and respectful process, while making sure books aren’t pulled from shelves just because someone disagrees with the views they contain.”

“For centuries, books have been a powerful tool of expression,” said Sen. Tizzy Lockman. “Libraries are important to our communities because they serve as a vessel and powerful outlet for this expression. The censorship we are seeing in federal initiatives aims to erase history and silence the diversity of opinion, and we must protect the rights of future generations. With the passage of HB 119, we are ensuring these essential tools and freedom to engage with the material of their choice are available for them.”

Justices skeptical of Colorado’s ‘conversion therapy’ ban

Amy Howe, “Majority of court appears skeptical of Colorado’s ‘conversion therapy’ ban,” SCOTUSblog (Oct. 7)

The Supreme Court on Tuesday morning appeared largely sympathetic to a Colorado licensed counselor who is challenging the state’s ban on conversion therapy – that is, treatment intended to change a client’s sexual orientation or gender identity – for young people. In Chiles v. Salazar, a majority of the justices seemed to agree with the counselor, Kaley Chiles, that the ban discriminates against her based on the views that she expresses in her therapy. But several justices suggested that, rather than striking the law down outright, the court should send the case back to the lower courts for them to take a closer look at whether the law passes constitutional muster.

[. . .]

One issue was whether Chiles could even bring her case, when Colorado has not sought to enforce the ban against her and says that it won’t do so. Justice Sonia Sotomayor contended that there was no “credible threat of prosecution,” as the Supreme Court’s cases require for a party to have standing. During the six years since the law had been enacted, she observed, there had not been any enforcement, “and we have the entity charged with administering the law saying we’re not going to apply it to your kind of … therapy.”

A second question arose from the state’s assertion that the ban regulates medical treatment, rather than speech. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson noted that there is a long historical tradition of regulating medical treatments, and she suggested that it would be “very odd” to think that two different medical professionals can provide different kinds of treatment for the same condition – one with talk therapy and one with medication – but the two kinds of treatment would receive different protection under the Constitution.

One question that may have remained open at the end of the argument was whether, even if a majority of the justices conclude that the law does discriminate against Chiles and strict scrutiny should therefore apply, the Supreme Court should apply strict scrutiny itself or instead send the case back to the lower courts for them to do so. Sotomayor and Jackson both suggested that the lower courts should consider the question for the first time rather than the justices.

Related

Ann E. Van Sickle, “Highlights of the Conversion Therapy Argument at the Supreme Court,” The New York Times (Oct. 7)

Nina Totenberg, “Supreme Court seems highly doubtful of limits on conversion therapy for minors,” NPR (Oct. 7)

Campus free speech event at NYU almost cancelled

Jonathan Adler, “A Discussion of ‘Campus Free Speech After October 7’ at NYU,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 10)

[Recently,] the Federalist Society sponsored a panel on “Campus Free Speech After October 7,” at New York University. The panel featured Judges Lisa Branch (Eleventh Circuit) and Roy Altman (S.D. Florida), former ACLU President Nadine Strossen, and the Manhattan Institute’s Ilya Shapiro.

As detailed in the Washington Free Beacon, this event (or, rather, a smaller event just featuring Ilya Shapiro) almost did not happen. NYU initially blocked the event, citing scheduling and security concerns, but ultimately relented once its actions were subject to public scrutiny.

The event did happen at NYU on October 7, and was live-streamed.

Zoom event this Friday on Trump, the media, and the First Amendment

Stuart Benjamin, “Trump, the Media, and the First Amendment,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 13)

This Friday at 12:30 pm ET I will be hosting an online discussion about whether actions by President Trump and his administration should affect how courts and scholars analyze the First Amendment’s application to the media.

The launching point is the Trump Administration threats to revoke broadcasters’ licenses, and President Trump’s lawsuits against media companies, which implicate important, and contested, First Amendment doctrines—particularly those developed in Red Lion v. FCC and FCC v. Pacifica Foundation (upholding FCC regulations of broadcasters’ speech), NRA v. Vullo and Murthy v. Missouri (addressing government pressure and threats of legal sanctions), and New York Times v. Sullivan (holding that in defamation suits public officials must prove that the speaker knew a statement was false or was reckless about its falsity).

Register at this link or scan the QR code above.

More in the news

“MIT President Says She ‘Cannot Support’ Proposal To Adopt Trump Priorities for Funding Benefits,” First Amendment Watch (Oct. 13)

Ari Cohn, “California wants to make platforms pay for offensive user posts. The First Amendment and Section 230 say otherwise,” Expression (Oct. 11)

“Judge Tosses Out Drake’s Defamation Lawsuit Against Label Over Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Not Like Us’,” First Amendment Watch (Oct. 10)

2025-2026 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

National Republican Senatorial Committee v. Federal Election Commission

Chiles v. Salazar (Argued Oct. 7)

Pending petitions

Petitions denied

Jones v. Lafferty (application for stay denied)

Last scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE.