The psychology of free speech

First Amendment News 495

The safe life is not worth living.

That provocative claim finds novel expression in my next two books, both works of fiction. Those works pay tribute to the value of risk. As I cast it in one of those forthcoming works:

Risk defines who we are or want to be. It is the oxygen that fills the lungs of the hero and heretic . . . To remove risk from life is to leave the human condition empty. . . Perhaps the greatest tragedy the ancient Greek gods could have inflicted on mortals was a life free of risk.

So much for teasers. I reference the idea of risk because I think it is germane to this post on the psychology of free speech and to the risks involved in defending it — risks I think worth taking, at least as a presumptive matter.

The paradoxical process

Free speech is a paradox. On the one hand, the very idea encourages us to seek the unattainable: full toleration of the views of others. While it makes for a worthy fantasy, it cuts against the grain of the human psyche. On the other hand, take it out of the psychological equation and what you have is tyranny over the minds of men and women.

Free speech is more a struggle than a realizable goal, more a work in constant motion than a destination arrived at, and more a formula for creating enemies than winning friends — at least, if faithfully practiced.

Mind you, this does not mean we should forsake it, but rather that we should be attentive to its real-world costs and thereby risk our comfort today in the name of a better tomorrow. Or at least that is the hope. In all of this, the focus is on the psychology of free speech and how it functions with competing human instincts. That said, our commitment to the free speech principle should remain an aspirational ideal for any variety of reasons.

“Congress shall make NO law…”

Despite what James Madison penned when he wrote the First Amendment, the “no law” prohibition has never been construed to be an absolute bar. Exceptions were crafted onto the 1791 guarantee (see e.g., United States v. Stevens). That fact was understood when the drafters of the early state constitutions added a “being responsible for the abuse” exception to their free expression clauses (see e.g., Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights, sect. 7) In certain respects, they (like every textualist since) appreciated the psychological dissonance of staunchly committing to the Madisonian ideal.

Why do I say this? Well, it’s natural to prefer one’s own over others. Both heart and mind tick that way. So when a Nat Hentoff type comes along and proclaims “Free Speech for Me — but not for Thee,” he is depicting a psychological default position, albeit one he contested. That partisan mindset informs much of the hypocrisy of the very crowds that yesterday preached the free speech gospel but today abridge it with wild abandon.

Take yesterday’s liberal free speech champions. They hailed that ideal when it came to Leftist causes, but remained terribly silent on everything from government jawboning to cancel culture. Or consider yesterday’s conservative free speech champions, who reveled in condemning Leftists’ abridgments of the First Amendment but today are disgustingly silent when it comes to the Trump Administration’s unparalleled violations of the First Amendment.

What explains this? Again, my answer: it’s natural to prefer one’s own over others. That’s just how the mind works, though in more sober moments, the free speech principle also urges the mind to consider its virtues as a “safety valve” to help curb social conflict. But moving the mind to that place takes work — typically more than the average psyche is willing to tolerate.

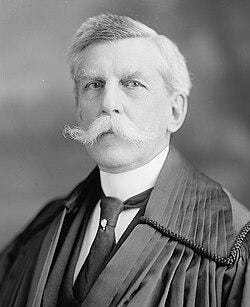

Justices Holmes and Black

Despite all his heroic free speech dissents, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes was more a Darwinian realist than a First Amendment absolutist. There is a passage of realist candor in his dissent in Gitlow v. New York (1925) that is rare to find in those who champion First Amendment primacy. Here is that passage:

Every idea is an incitement. It offers itself for belief, and, if believed, it is acted on unless some other belief outweighs it or some failure of energy stifles the movement at its birth. The only difference between the expression of an opinion and an incitement in the narrower sense is the speaker’s enthusiasm for the result. Eloquence may set fire to reason. But whatever may be thought of the redundant discourse before us, it had no chance of starting a present conflagration. If, in the long run, the beliefs expressed in proletarian dictatorship are destined to be accepted by the dominant forces of the community, the only meaning of free speech is that they should be given their chance and have their way…

Note here that the Darwinian-minded Holmes understood that the free speech principle might lead to a “dictatorship.” He did not sugarcoat that idea. Think of such realism as free speech unbound — that is, the principle is untethered from any competing psychological safe-harbor mooring.

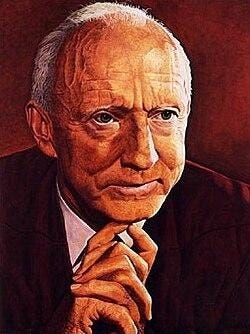

By contrast, consider Justice Hugo Black, the champion of free speech absolutism — until such absolutism hit too close to home, as in the protests cases of the 1960s, such as Cox v. Louisiana (1965) and Tinker v. Des Moines (1969). He feared what such protests were doing to his beloved nation.

While Holmes’ dissents are habitually defended by free speech advocates, it is largely because they fail to see the dark side of his Gitlow dissent. As for those who habitually criticize Black’s breach of the free speech principle, they often do so because they fail to appreciate the psychological factor at work there.

Two minds at work: One bold and risk-averse, the other fickle but self-protective. So ask yourself, whose view do you prefer? Then ask yourself, which one do you actually practice?

Freeing speech

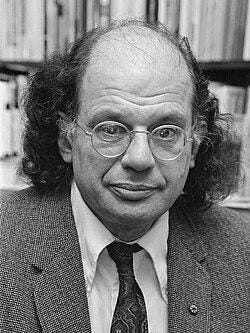

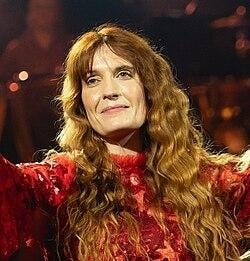

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness . . .

The magic and the misery, madness and the mystery.

Oh, what has it done to me? Everybody scream!

So much of First Amendment talk is fixated on rationality, on Enlightenment-like ideas. Oh yes, there are those self-realization and self-expression tenets that blend into the conceptual mix. Close, but not close enough, to the outrageously poetic side of the psychological ledger. That is: What about speech that screams out to be freed from the norms of convention? Or what about speech that wants to do no more than howl at the moon in the face of a world overwhelmed by madness?

We live in such times — times that test men and women’s souls. The need to scream, to vomit out the agony of struggling to survive in a nation drowning in insanity, is part of the psychology of speech. Nothing rational, nothing communal, nothing doctrinal — just an unrelenting need to free speech from normalcy, from the prescribed ways to speak.

Romantic and insanely reckless? Perhaps, but so what? Being normal is insufficient to nourish the needs of the inner self; the fact is, too often it leaves it starving. For some, there is no other option but to enter the marketplace of ideas (a wildly exaggerated ideal) and yell “FUCK IT!” until one’s lungs are emptied.

I am, therefore I speak, therefore I scream. It’s just that damn simple.

Psychological babble?

If you want to piss off your friends, just champion free speech sans any partisan gloss. Don’t believe me? Just consider the heroic and heretical life and times of one Greg Lukianoff (see e.g., Natalie Kitroeff, “The Lonely Work of a Free-Speech Defender” in The New York Times’ “The Daily” podcast). In some important respects, Greg is the kind of person championed in my forthcoming precarious works of fiction — someone whose character plights fluctuate between commendation and condemnation.

So, where am I going with all of this psychological “babble”? Well, what I am not urging is any rejection of the Madisonian ideal. What I am stressing is that it is natural for people to be hypocritical when it comes to tolerating free speech. That is the psychological default position. Then again, that psychological condition need not be absolute; it can be better informed by appreciating the value of stepping outside of one’s comfort zone. And that is because to be fully human we must also embrace risk — up to a point.

Bottom line: When Madison argued for “no law,” he was asking a hell of a lot of us, both as a political principle and as a psychological one. More must be said, but you’ll have to wait until my Forbidden Freedom novel comes out — followed by my collection of short stories titled I Take My Chances.

Court denies review in book removal case

Leaving the Fifth Circuit’s ruling in place erodes the most elemental principles of free speech and allows state and local governments to exert ideological control over the people with impunity. The government has no place telling people what they can and cannot read.

This past Monday, the Court denied review in Little v. Llano County. The issue raised in that case was whether certain book-removal decisions are subject to scrutiny under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

The case arose against the backdrop of the urging of a handful of private citizens to remove seventeen books from the county library’s shelves. A district court found that those book-removal decisions were motivated by a desire to censor particular viewpoints.

In her petition for review, Elizabeth Prelogar set out the general facts as follows:

This case presents a critically important First Amendment question that has divided the circuits. In recent years, state and local governments have increasingly removed books from public libraries because they disagree with the ideas those books promote. Here, for instance, the public library in Llano County, Texas, removed books — including publicly acclaimed nonfiction works and memoirs — because they espoused ideas about racial justice and gender identity that government officials deemed “inappropriate.” Such a viewpoint-based book ban violates the “bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment”: “the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.” Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 414 (1989).

The removed books include: a work examining the history of racism in the United States, which the New York Times Book Review lauded as “an instant American classic and almost certainly the keynote nonfiction book of the American century thus far,” Dwight Garner, Isabel Wilkerson’s ‘Caste’ Is an ‘Instant American Classic’ About Our Abiding Sin, N.Y. TIMES (Jan. 21, 2021); a work chronicling the Ku Klux Klan, its origins, and its growth in the United States, which has been called “an exemplar of history writing and a must for libraries,” They Called Themselves the K.K.K: The Birth of an American Terrorist Group, KIRKUS (May 31, 2010); several award-winning, coming-of-age novels or memoirs; and a classic, Caldecott-Medal-winning children’s picture book, (In the Night Kitchen, by Maurice Sendak).

Amicus briefs in support of the Petitioner were filed by:

Related

Eugene Volokh, “S. Ct. Declines to Rehear Fifth Circuit’s Holding That Public Libraries May Select/Remove Books Based on Viewpoint,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Dec. 8)

Forthcoming book on banning books

Samuel Cohen, “Banning Books in America: Not a How-to,” Bloomsbury Academic Press (Feb. 19, 2026)

This is a book about banned books in the U.S. — about reading them, teaching them, and lending them under the shadow of political pressure not to.

Banning Books in America features novelists on banning and being banned, arguments about the histories and politics of book banning, readings of banned books in national and international contexts, and responses to new legislation by anti-censorship advocates, teachers, and librarians. Together, these writers and educators provide a view from the trenches of the wars on reading. They offer, if not a single blueprint, models for how to think about what it means to ban books and how to fight back against the forces that would ban them.

This book shows that at the heart of this issue is the question of what books mean to people. Some Americans are determined to decide which books other Americans shouldn’t get to read. Why these books? Why now? Anyone who seeks to answer these questions must examine the context, historical and current, in which Americans allow this to happen.This is a book about book banning in America, and so it is a book about America.

Samuel Cohen is Associate Professor of English at the University of Missouri, Columbia, USA, where he teaches a course on banned books. He is the author of After the End of History: American Fiction in the 1990s (Choice Outstanding Academic Title, 2010) and co-editor of The Legacy of David Foster Wallace (2012) and The Clash Takes on the World (Bloomsbury, 2017). He is the series editor of The New American Canon: The Iowa Series in Contemporary Literature and Culture.

Comstock’s crusade: More on ‘certainty is the censor’s servant’

After last week’s post, I “recalled” that someone else had made the same point in connection with Anthony Comstock’s moral crusade. Fact is, FIRE Chief Counsel Robert Corn-Revere’s point is spot on, and well made:

Robert Corn-Revere, “The Mind of the Censor and the Eye of the Beholder,” Cambridge University Press (2021)

Ten Rules for the Morals Entrepreneur

Rule #1: Exhibit Moral Certainty.

Comstock didn’t have to work at this attribute, as belligerent sanctimoniousness came to him quite naturally. The thing about being on a holy mission is that the crusader never doubts the righteousness of the cause, and that was certainly true of Anthony Comstock. The man was, in the words of his biographers, “a four-square granite monument to the Puritan tradition.” Comstock firmly believed “in himself and in his work to the end.”

His writings exhibited an unshakable certitude. Comstock described the statutes adopted in his name as “the most righteous laws ever enacted,” calling them a “barrier between youth and moral death.” When he acted to suppress Margaret Sanger’s pamphlet “Family Limitation,” he called the publication “contrary not only to the law of the State, but to the law of God.”

In his prolific writings documenting his campaign for moral purity, Comstock said his purpose in writing was “in the hope that the blind be made to see and the erring to correct their ways.” He said his goal was to “appeal for greater watchfulness on the part of those whose duty is to think, act, and speak for that very large portion of the community who have neither the intellect nor judgment to decide what is wisest and best for themselves.”

Comstock was so wrapped up in the belief he was on god’s holy mission as to blur the distinction between deity and man. His grandiosity was revealed most when in the throes of one of his perennial bouts of self-pity brought on by what he saw as unjust and uninformed attacks on his character. When warned that his reputation would be maligned by those seeking to repeal the postal law, Comstock replied, “I cannot expect to have better treatment than our blessed Master.”

Perhaps Oliver Wendell Holmes had Anthony Comstock in mind when he wrote in 1919 that persecution of disfavored ideas and expression is perfectly logical if “you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart.” But where Holmes encouraged self-doubt and caution as a hedge against tyranny, Comstock pushed in the opposite direction. Like Samson’s flowing locks, the source of Comstock’s strength was his cocksureness. The way to tell a censor, according to Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, is by their level of self-assurance. So it was with Comstock. And so it is with all who believe his or her conception of truth, morality, or sensitivity to offensiveness can override the right of another individual to write or speak. Comstock’s creed was the mirror opposite of words often attributed to Thomas Jefferson, that “eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” For the vice hunter, Comstock wrote, “eternal vigilance is the price of moral purity.” No doubt about it.

Related

Marie Fiala, Alex Kozinski, John P. Coale, and Andrei Popovici’s amicus brief in Trump v. Twitter (9th Cir., 2022)

Since taking office, the Biden administration has acted aggressively to bully, encourage, and collude with social media companies to censor speech that departs from the “party line” regarding COVID vaccines and treatments, one of the categories of disfavored speech.

Apple said to have yielded to government pressure to remove ICE tracking app

Tripp Mickle, “App That Tracks ICE Raids Sues U.S., Saying Officials Pressured Apple to Remove It,” The New York Times (Dec. 8)

The developer of ICEBlock, which notifies users of ICE agent sightings, said Attorney General Pam Bondi censored his free speech.

For six months, Apple distributed an app called ICEBlock that allowed users to alert people when they saw Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. But after the Trump administration complained that the app endangered officers, Apple removed it.

On Monday, the app developer, Joshua Aaron, sued top Trump administration officials, accusing them of pressuring Apple to stifle his free speech and his right to create, distribute, and promote ICEBlock.

The suit, which was filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, claimed that Attorney General Pam Bondi abused the government’s power when the Justice Department contacted Apple and demanded it remove the app, which she said she had done in a statement to Fox News in October. She said Apple had removed the app after her request.

More in the news

Lisa Kashinsky, “Rahm Emanuel says US should follow Australia’s youth social media ban,” Politico (Dec. 9)

“Florida Governor Declares Muslim Civil Rights Group a Terrorist Organization,” First Amendment Watch (Dec. 9)

“[The executive] order instructs Florida agencies to prevent the two groups and those who have provided them material support from receiving contracts, employment, and funds from a state executive or cabinet agency.”

BrieAnna J. Frank, “Ex-FBI agents just sued Kash Patel. Why their case could prove complex,” USA Today (Dec. 9)

Garrett Gravley, “Trinity College bans political activism over chalkboard messages,” FIRE (Dec. 8)

Eugene Volokh, “Speech to the Public Laying Out Legal Theories Isn’t Unauthorized Practice of Law,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Dec. 8)

Peter Brown, “Mental Health Warnings Confront the First Amendment,” Law.com (Dec. 7)

“Ballot Committee Fights Speech Mandate at the Colorado Supreme Court,” Institute for Free Speech (Dec. 5)

Samuel J. Abrams, “If free speech only matters when convenient, it isn’t free at all,” FIRE (Dec. 1)

2025-2026 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

Chiles v. Salazar (argued: Oct. 7)

Olivier v. Brandon (argued: Dec. 3)

First Choice Women’s Resource Centers, Inc. v. Platkin (argued: Dec. 2)

National Republican Senatorial Committee v. Federal Election Commission (argued: Dec. 9)

Pending petitions

360 Virtual Drone Services LLC v Ritter

Emergency docket (‘Shadow docket’)

Chamber of Commerce v. Sanchez (application withdrawn)

Petitions denied

Cambridge Christian School, Inc. v. Florida High School Athletic Association, Inc.

Hartzell v. Marana Unified School District

Evans Hotels, LLC v. Unite Here! Local 30

Last Scheduled FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of FIRE.